Problems here in Thailand got me thinking. Extreme weather events. 1st up, Canada and their fires.

NASA - Extreme Weather and Climate Change

How do scientists determine if changes in extreme weather events are linked to climate change?

Scientists use a combination of climate models (simulations) and land, air, sea, and space-based observations to research how extreme weather events change over time. First, scientists examine historical records to determine the frequency and intensity of past events. Many of these long-term records date back to the 1950s, though some start in the 1800s. Then scientists use climate models to see if the number or strength of these events is changing, or will change, due to increasing greenhouse gases when compared to what has happened historically.

NASA Science Live: Climate Edition - Extreme Weather

_________

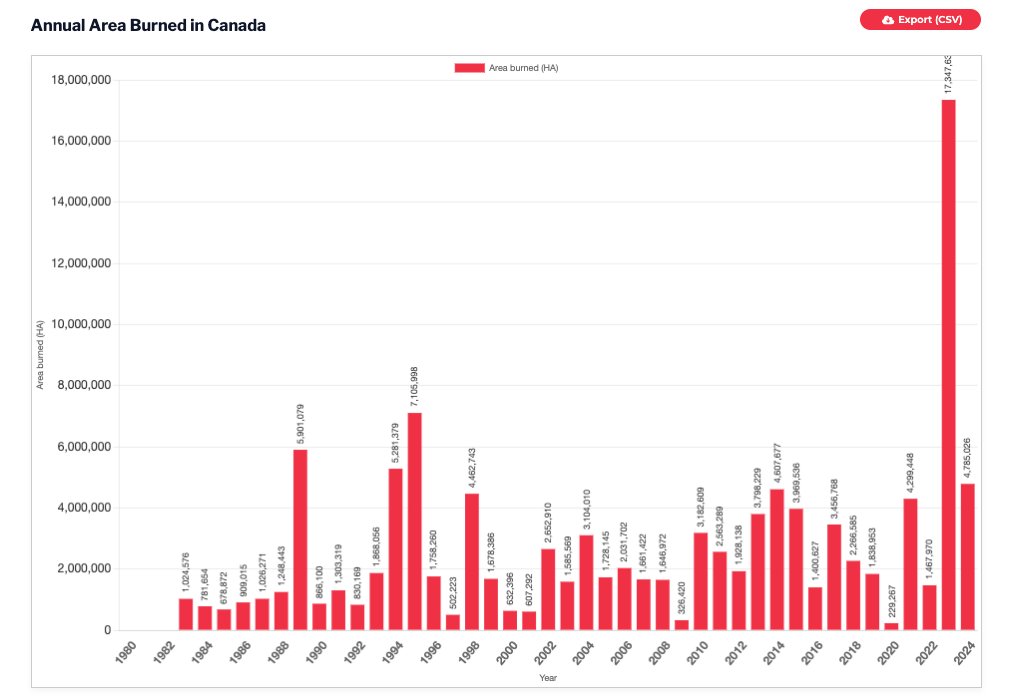

Largest study of 2023 wildfires finds extreme weather fuelled flames coast to coast

The largest study of Canada's catastrophic 2023 wildfire season concludes it is "inescapable" that the record burn was caused by extreme heat and parching drought, while adding the amount of young forests consumed could make recovery harder.

And it warns that the extreme temperatures seen that year were already equivalent to some climate projections for 2050.

"It is inescapable that extreme heat and moisture deficits enabled the record-breaking 2023 fire season," says the study, published Tuesday in the journal Nature Communications.

That season burned 150,000 square kilometres -- seven times the historical average -- forced 232,000 Canadians from their homes and required help from 5,500 firefighters from around the world, as well as national resources and the military. Smoke drifted as far as western Europe.

"In 2023, we had the most extreme fire weather conditions on record over much of the country," said Piyush Jain, a scientist with Natural Resources Canada. "I think the connection is pretty clear."

The paper finds that although there were differences in how the 2023 fire season played out in Western, Northern, Eastern and Atlantic Canada, the underlying causes were the same. That season had more extreme fire weather -- defined as a combination of heat and drought that exceeds 95 per cent of all fire season days -- than any year since records began in 1940.

Temperatures across the country averaged 2.2 degrees above normal during the fire season.

Results 1 to 9 of 9

Thread: Extreme Weather

-

25-08-2024, 02:01 PM #1

Extreme Weather

Keep your friends close and your enemies closer.

-

29-08-2024, 05:03 PM #2

Typhoon Shanshan: Japan prepares for ‘major disaster’ as storm makes landfall

Japan’s strongest typhoon of the year has made landfall in the country’s south-west, bringing torrential rain and winds of up to 252 km/h (157 mph), strong enough to destroy homes.

The meteorological agency said Typhoon Shanshan, referred to in Japan as Typhoon No 10, made landfall on the island of Kyushu at around 8am. The power company said 254,610 houses were already without electricity.

The meteorological agency predicted 1,100mm (43in) of precipitation in southern Kyushu in the 48 hours to Friday morning, around half the annual average for the area, which comprises Kagoshima and Miyazaki prefectures.

Authorities issued a rare special typhoon warning for most parts of Kagoshima, a prefecture in southern Kyushu. Residents in at-risk areas have been urged to remain on high alert, with transport operators and airlines cancelling trains and flights.

The potential for major damage is high given Shanshan’s sluggish speed. The storm is moving northwards at just 15km/h, the meteorological agency said.

There have already been reports of deaths in landslides – a major hazard in mountainous areas – while tens of thousands of people have been advised to evacuate.

“Typhoon Shanshan is expected to approach southern Kyushu with extremely strong force through Thursday,” chief cabinet secretary Yoshimasa Hayashi told reporters earlier. “It is expected that violent winds, high waves and storm surges at levels that many people have never experienced before may occur.”

The approach of the storm prompted automaker Toyota to suspend production at all 14 of its factories. Other major car manufacturers have followed suit, according to the Kyodo news agency.

Three members of a family died after a landslide buried a house in the central city of Gamagori, Kyodo reported early on Thursday, citing local government officials.

The victims included a couple in their 70s and a son in his 30s, while two adult daughters in their 40s were injured, Kyodo added.

The agency also issued its highest “special warning” for violent storms, waves and high tides in parts of the Kagoshima region, with authorities there advising 56,000 people to evacuate.

Video footage on public broadcaster NHK TV showed roof tiles being blown off houses, broken windows and felled trees.

“Our carport roof was blown away in its entirety. I wasn’t at home when it happened, but my kids say they felt the shaking so strong they thought an earthquake happened,” one resident in Miyazaki told NHK. “I was surprised. It was completely beyond our imagination.”

The warnings indicate the “possibility that a major disaster prompted by [the typhoon] is extremely high,” Satoshi Sugimoto, chief forecaster of the meteorological agency, told a news conference.

Japan Airlines cancelled 172 domestic flights and six international flights scheduled for Wednesday and Thursday, while ANA scrapped 219 domestic flights and four international ones across Wednesday, Thursday and Friday.

The cancellations affected about 25,000 people.

Kyushu Railway said it would suspend some bullet train services between Kumamoto and Kagoshima Chuo from Wednesday night and warned of further possible disruption. Trains between Tokyo and Fukuoka, the most populous city on Kyushu, may also be cancelled depending on weather conditions this week, other operators said.

Shanshan comes in the wake of Typhoon Ampil, which disrupted hundreds of flights and trains this month. Despite dumping heavy rain, it caused only minor injuries and damage.

Ampil came days after Tropical Storm Maria brought record rains to northern areas.

Japan has issued special typhoon warnings only three times in the past. The first came in July 2014, when a strong typhoon brought record-breaking waves to the southern prefecture of Okinawa before moving north, killing three people in landslides in Nagano prefecture.

In October 2016, authorities issued a similar warning for Okinawa’s main island. The typhoon moved north over the sea west of the southernmost main island of Kyushu.

The most recent special typhoon warning came in September 2022 – the first time the warning had been issued outside Okinawa prefecture, according to public broadcaster NHK.

Like the typhoon that made landfall in southwestern Japan on Thursday morning, the storm moved slowly, giving it time to cause extensive damage to homes. Five people died in the disaster.

Typhoons in the region have been forming closer to coastlines, intensifying more rapidly and lasting longer over land due to the climate crisis, according to a study released last month.

Human-caused climate breakdown has increased the occurrence of the most intense and destructive tropical cyclones (though the overall number per year has not changed globally). This is because warming oceans provide more energy, producing stronger storms.

Extreme rainfall from tropical cyclones has increased substantially, as warmer air holds more water vapour. For example, the amount of rainfall produced by Hurricane Harvey in Texas in 2017 would have been all but impossible without the record-warm ocean water in the Gulf of Mexico.

Coastal storm surges are also higher and more damaging due to the sea level rise driven by climate breakdown. For example, the devastating storm surge from Typhoon Haiyan, which hit the Philippines in 2013, was about 20% higher due to human-caused climate breakdown.

-

30-08-2024, 09:00 AM #3

Millions told to evacuate as typhoon batters Japan

Japan has issued its highest level alert to more than five million people after the country was hit by one of its strongest typhoons in decades.

At least four people have been killed and more than 90 injured after Typhoon Shanshan made landfall in the country’s south-west. Hundreds of thousands of people have been left without power.

The level five order issued in parts of the southern island of Kyushu told residents to take immediate life-saving action by moving to a safer location or seeking shelter higher in their homes. In other areas, people have been advised to leave.

After making landfall, the typhoon weakened to a severe tropical storm and is pummelling its way north-east, bringing torrential rain and severe disruption to transport services.

Shanshan landed in Kagoshima prefecture, in the southern island of Kyushu, at around 08:00 local time on Thursday (23:00 GMT Wednesday), the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) said.

It has left a trail of destruction in its wake, with many buildings damaged and windows shattered by flying debris, trees uprooted and cars overturned.

Late on Tuesday, three people from the same family - a couple in their 70s and a man in his 30s - were killed by a landslide in central Japan ahead of the typhoon's arrival. Their home in Gamagori was swept away, while two other female relatives were rescued.

A fourth person was confirmed dead by police on Thursday. The 80-year-old man from Tokushima prefecture was trapped after the roof of a house collapsed about 17:30 local time (08:30 GMT), according to Japan’s national broadcaster NHK.

The fire brigade rescued the man around 50 minutes after the incident but he later died in hospital. The JMA recorded 110mm of rainfall in the area around the time of the incident.

The agency has issued its rare "special warning" for the most violent storms, warning of landslides, flooding and large-scale damage. High winds of up to 252 km/h (157mph) have been reported on Kyushu.

Most of the evacuation orders are in place for the southern island, but some were also issued for central Japan.

Videos online show large trees swaying, tiles blown off houses, and debris being thrown into the air as heavy rains lashed the island.

Major carmakers like Toyota and Nissan shut down their plants, citing the safety of employees as well as potential parts shortages caused by the storm.

Typhoon Shanshan Pummels Japan

According to University of Tokyo climate scientist Hisashi Nakamura, the typhoon intensified between August 25 and 27, fueled by unusually warm water in the Philippine Sea. During that time, sea surface temperatures were around 30 degrees Celsius (86 degrees Fahrenheit).

-

30-08-2024, 05:43 PM #4

Last few days of Winter here, and Australia just had its hottest August days EVER recorded. It's not just warm or hot...it's like the middle of Summer. I'm talking 36 Celsius. Luckily the humidity is low.

-

30-08-2024, 10:04 PM #5

If I had to guess, I'd say extremely lengthy c+p will be prevalent in all areas, and otherwise perfectly equable posters will be privately wishing that their source dies out in time for a bright and breezy weekend.

-

30-09-2024, 10:13 AM #6

Helene leaves "unimaginable" destruction in 5 states as death toll rises

Hurricane Helene has left officials in five southeastern states grappling to respond to the widespread destruction it caused after hitting Florida as a Category 4 story last week, as the death toll continues to rise.

The big picture: Officials on Sunday confirmed 30 deaths in the flood-hit Buncombe County, western North Carolina, where Asheville saw historic water level rises  bringing the number of storm-related deaths across six states to at least 91, per AP.

- Officials also confirmed storm-related deaths in Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, Tennessee and Virginia, as search and rescue teams continued to respond to the fallout from the hurricane that struck Florida late Thursday before moving into Georgia, the Carolinas and Tennessee.

- Widespread outages still affected hundreds of thousands of people in multiple states Sunday evening, including North and South Carolina and Georgia.

State of play: Underscoring the widespread threats the former Hurricane Helene posed, the Biden-Harris administration approved emergency requests for federal assistance from Florida, Georgia, North and South Carolina and Alabama ahead of the storm's landfall.

- FEMA administrator Deanne Criswell told CBS News Sunday that the five states affected by the storm "are going to have very complicated recoveries, but we will continue to bring those resources in to help them, technical assistance as they're trying to identify the best ways to rebuild."

- She noted on CBS' "Face the Nation" there's "historic flooding" in North Carolina, particularly in the state's west.

- "I don't know that anybody could be fully prepared for the amount of flooding and landslides they are having right now," Criswell said.

- Pamlico County Emergency Management in a Saturday Facebook post described the damage from the remnants of the storm in Chimney Rock, some 41 miles southeast of Asheville, as "unimaginable."

Zoom in: Criswell joined Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis to survey damage in hurricane-hit state on Tuesday and she was surveying damage in Valdosta, Georgia, on Sunday. She'll meet with leaders in flood-affected North Carolina communities on Monday.

- President Biden told Criswell when she briefed him on the ongoing impacts in the storm-affected states that he plans to travel this week affected communities "as soon as it will not disrupt emergency response operations," per a Sunday evening White House pool report.

- Vice President Kamala Harris also intends to visit impacted communities once this is possible, according to a report from poolers traveling with the Democratic presidential nominee.

- Former President Trump's presidential campaign announced plans to visit Valdosta on Monday.

By the numbers: Over 779,000 customers were without power in South Carolina and another 586,000 others in Georgia were without electricity on Sunday night, per poweroutage.us.

- More than 481,000 in N.C., nearly 138,000 in Florida and almost 104,000 in Virginia also had no power, according to the utility tracker.

Between the lines: Hurricanes are increasingly likely to become more intense, and studies show human-caused climate change is a major driver of this.

- Hurricane Helene was part of a growing trend of storms that have undergone rapid intensification. This one was among eight other landfalling storms in the U.S. that rapidly intensified by at least 35 mph in 24 hours before landfall.

- The extreme intensification rate was due in large part to hot ocean surface temperatures in the Gulf of Mexico, along with ocean heat content values. Research shows climate change is boosting global ocean temperatures.

- Criswell noted on CBS that in the past, "when we would look at damage from hurricanes, it was primarily wind damage, with some water damage."

- Now, "we're seeing so much more water damage, and I think that is a result of the warm waters, which is a result of climate change."

Tariq Scott Bokhari: Went to help in the Lake Lure/Chimney Rock area today, and itÂs hard to describe - never seen anything like this. Post apocalyptic. ItÂs so overwhelming you donÂt even know how to fathom what recovery looks like, let alone where to start. Going to be a long path to recovery that all levels of stakeholders are going to be needed. https://twitter.com/FinTechInnov8r/s...50451998703951

https://www.axios.com/2024/09/30/hur...t-flood-damage

-

11-11-2024, 04:57 PM #7

Extreme weather cost $2tn globally over past decade, report finds

Violent weather cost the world $2tn over the past decade, a report has found, as diplomats descend on the Cop29 climate summit for a tense fight over finance.

The analysis of 4,000 climate-related extreme weather events, from flash floods that wash away homes in an instant to slow-burning droughts that ruin farms over years, found economic damages hit $451bn across the past two years alone.

The figures reflect the full cost of extreme weather rather than the share scientists can attribute to climate breakdown. They come as world leaders argue over how much rich countries should pay to help poor countries clean up their economies, adapt to a hotter world and deal with the damage done by increasingly violent weather.

“The data from the past decade shows definitively that climate change is not a future problem,” said John Denton, secretary-general of the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC), which commissioned the report. “Major productivity losses from extreme weather events are being felt in the here and now by the real economy.”

The report found a gradual upward trend in the cost of extreme weather events between 2014 and 2023, with a spike in 2017 when an active hurricane season battered North America. The US suffered the greatest economic losses over the 10-year period, at $935bn, followed by China at $268bn and India at $112bn. Germany, Australia, France and Brazil all made the top 10.

When measured a person, small islands such as Saint Martin and the Bahamas saw the greatest losses.

Fire, water, wind and heat have wiped more and more dollars off government balance sheets as the world has grown richer, people have settled in disaster-prone regions, and fossil fuel pollution has baked the planet.

But until recent years, scientists struggled to estimate the extent of the role that humans played by warping extreme weather events with planet-heating gas.

Climate breakdown was responsible for more than half of the 68,000 heat deaths during the scorching European summer of 2022, a study found last month, and doubled the chance of the extreme levels of rainfall that hammered central Europe this September, an early attribution study found. In some other cases, researchers found only mild effects or did not observe a climate link at all.

Ilan Noy, a disaster economist at Victoria University of Wellington, who was not involved in the ICC study, said its numbers align with previous research he had done but cautioned that the underlying data did not capture the full picture. “The main caveat is that these numbers actually miss the impact where it truly matters, in poor communities and in vulnerable countries.”

A study Noy co-wrote last year estimated the costs of extreme weather attributable to climate breakdown at $143bn a year, mostly due to loss of human life, but was limited by data gaps, particularly in Africa.

“Most of the impact that is counted is in high-income countries – that’s where asset values are much higher, and where mortality from heatwaves is counted to be much larger,” said Noy. “Clearly, the losses of homes and livelihoods in a poor community in poor countries are more devastating in the longer term than losses in wealthy countries where the state is able and willing to assist in recovery.”

The ICC urged world leaders to act faster to get money to countries that needed help to cut their pollution and to develop in ways that can withstand the shocks of violent weather.

“Financing climate action in the developing world shouldn’t be seen as an act of generosity by the leaders of the world’s richest economies,” said Denton. “Every dollar spent is, ultimately, an investment in a stronger and more resilient global economy from which we all benefit.”

-

19-11-2024, 03:05 PM #8

How do we know that the climate crisis is to blame for extreme weather?

It is a crucial question: is the climate crisis to blame for the extreme weather disasters taking lives and destroying homes around the world. But it has not been an easy one to answer. How much is due to global heating, how much is just the severe weather that has always happened?

The good news is that the scientific techniques used to untangle that question – called climate attribution – are now well established. The bad news is what they reveal: the studies show that the burning of fossil fuels has changed the climate so dramatically that heatwaves, floods and storms are now hitting communities with a severity and frequency never seen during the entire development of human civilisation.

What are attribution studies?

There are three approaches, used in combination to give the most reliable results. All compare the present with the past in order to calculate the increased frequency or severity of events. Weather data from the overheated present and the cooler past, when available, can be compared to see how many times more an extreme event happens today. Climate models can be used in a similar way to compare modern and preindustrial climates. Thirdly, climate models can also simulate the climate from, say, 1900 to the modern day, with slowly rising human-caused emissions. This enables scientists to detect trends in extreme weather, as well as the overall change in likelihood.

What have the studies found?

The most striking findings are of extreme heatwaves that would have been impossible without global heating, because they have no historical precedent and do not happen in model simulations without the added heat from human-caused climate change. That is as close to saying global heating caused the heatwave as makes no difference. At least 24 previously impossible heatwaves have already struck around the world, from Europe to North America, Africa and east Asia.

What about other events?

Many more extreme weather events have been made significantly worse, or more likely, by global heating. That means hotter heatwaves, more intense rains, stronger gale-force winds. Of the 744 attribution studies in a database produced by Carbon Brief, the most comprehensive that exists, three-quarters found that global heating had a significant impact.

Which extreme weather events are most supercharged by the climate crisis?

Heatwaves have been the most studied extreme weather events, with more than 200 analyses, and 95% were made more severe or more likely. Not a single one was made less likely.

What about floods and droughts?

Deluges of rain can be analysed relatively easily but floods are more complex, because their occurrence is also affected by human-built defences and the topography of the land. Nonetheless, of the 177 assessments of rain and flooding events, more than 60% were worsened by global heating, while 11% were made less likely, and the rest showed no influence or were inconclusive. Almost 70% of the 106 drought events were made more likely, with only one made less likely.

Can attribution analyses look at death tolls from extreme weather?

Yes. It is more complicated but a growing number of studies are estimating the influence of global heating on the impacts of extreme weather events, not just the events themselves. Of 33 such studies, 91% showed impacts made worse by global heating.

One found that one in three newborn babies who died due to heat in some countries would have survived if global heating had not pushed temperatures beyond normal bounds. Another found approximately 100,000 heat-related deaths in summer every year due to the climate crisis.

Other studies found that Hurricane Harvey would not have flooded 30%-50% of the US properties that it did in 2017 without global heating, and that four major floods in the UK would have caused only half the $18bn (£14.3bn) of wrecked buildings were it not for human-caused climate change.

The pre-existing vulnerability of communities is also a critical factor in how damaging climate impacts are. People in poorer nations with less resilient homes and fewer resources suffer far more than those in rich nations.

What about changes to snow storms and freezing snaps?

Almost 60 of these have been assessed, finding unsurprisingly that in most cases that global heating made such weather milder or less likely.

Can attribution studies be used to hold polluters to account?

Yes. Such studies are increasingly being used as evidence of responsibility for climate damage in landmark legal cases, such as Juliana v United States and Lluiya v RWE. Attribution science is also being used to inform negotiations over funding for the UN’s “loss and damage” fund, which would finance the rebuilding of communities after climate disasters.

What can be said if no attribution study has been done?

Scientists have the capacity to assess only a small fraction of all extreme weather events. Researchers at the World Weather Attribution initiative use criteria to decide which to analyse, including how many people are affected and how much damage has been caused, as well as the availability of data.

However, enough research has now been done to make very confident statements about most extreme weather events. Scientific methods can also give a real-time assessment of how much more likely a temperature was made by global heating anywhere in the world.

Extreme rainfall is also more common and more intense across most of the world, particularly in Europe, most of Asia, central and eastern North America, and parts of South America, Africa and Australia. For coastal flooding, every event is more likely than it would otherwise have been, because human-caused climate breakdown is driving sea level rise. Droughts and wildfires are also becoming more common and severe in many places.

Continuing attribution research will reveal even more about how much global heating has changed the world of extreme weather. But it is already very clear that the climate crisis is here and causing immense damage today.

-

01-12-2024, 12:35 PM #9

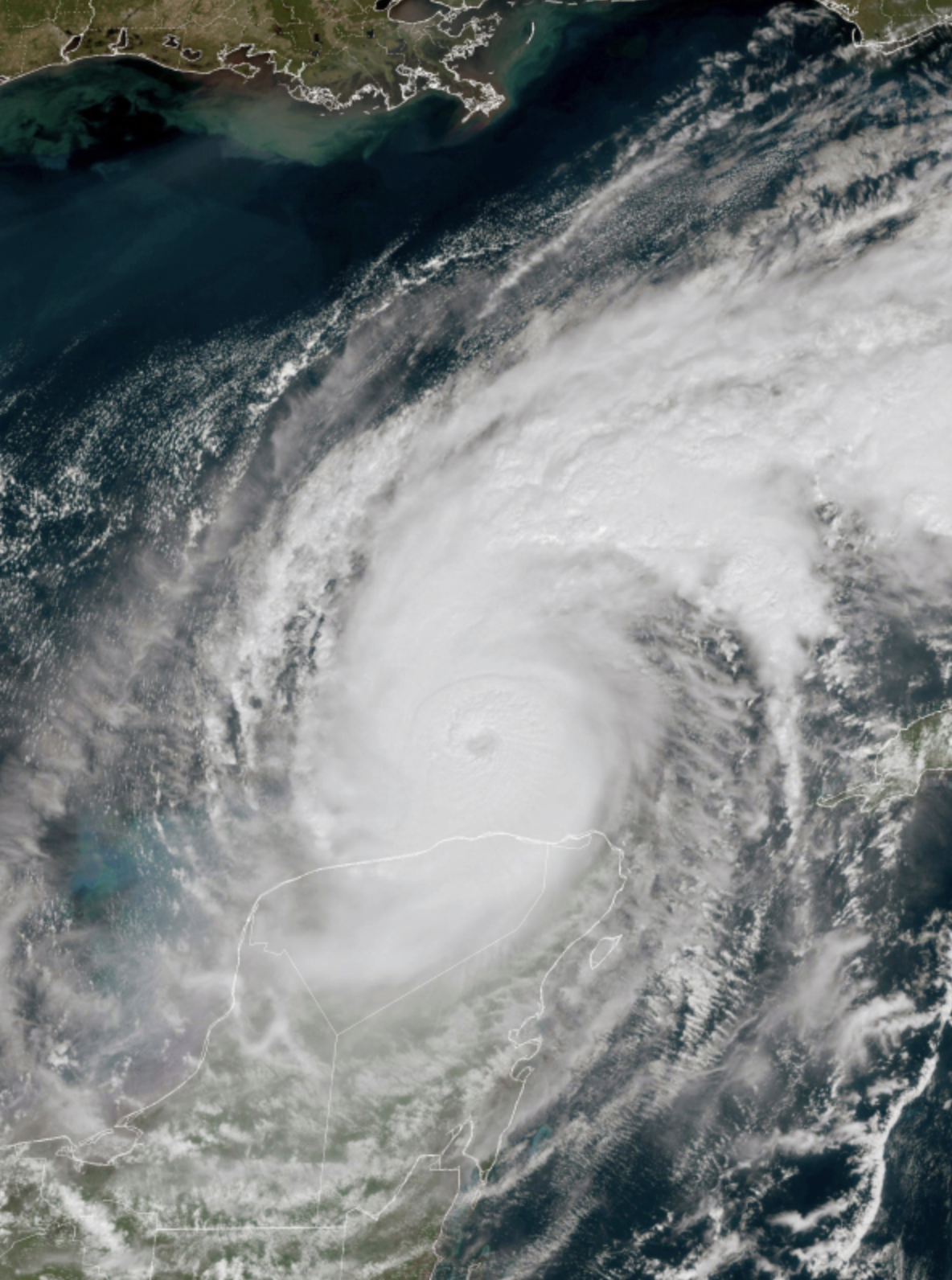

Reflections on the 2024 Atlantic Hurricane Season | MICHAEL E. MANN

Now that the 2024 Atlantic hurricane season seems to be coming to a close, it is worth reflecting on what transpired and what we might learn from it.

By most measures, it was an active, destructive and--unfortunately--deadly storm season, with 11 tropical cyclones reaching hurricane strength, 5 of them making landfall on the U.S., two of them--Helene and Milton--as major hurricanes. One particularly notable feature was the extreme rapid intensification of several storms, including Beryl, which intensified from a tropical storm to a hurricane in under 24 hours, Helene which intensified from a weak tropical storm to a cat 4 major hurricane in 48 hours, becoming the strongest storm on record to make landfall on the Florida "Big Bend" region, and Milton, which went from cat 1 to a 185 mph monster cat 5 in under 24 hours. Most remarkable of all, however, was Oscar which the National Hurricane Center identified as a small tropical disturbance off the coast of the Dominican Republic at 8 AM EDT on October 19th, only to upgrade it to a Hurricane 5 hours later. It left a trail of destruction after making landfall in eastern Cuba, resulting in a half dozen fatalities. Unfortunately, we shouldn't be surprised--this is part of a steady trend toward rapid intensification and was predicted a number of years ago by leading hurricane scientist Kerry Emanuel of MIT as a consequence of warming oceans.

The increased intensity and destructive potential of these storms too can be attributed to human-caused warming. A recent study found that human greenhouse warming substantially boosted the intensity of the 2024 storms, concluding that the two category 5 storms--Beryl and Milton--likely would not have reached that status in the absent of human-caused warming. Indeed Milton nearly breached the threshold of 192 mph sustained winds argued by one recent study to constitute a whole new "category six" caliber of hurricanes that has emerged in an era of unprecedented ocean warmth. A separate study estimated that the deadly flooding in the southeastern U.S. from hurricane Helene was increased by 50% by human-caused warming.

While the 2024 hurricane season was unprecedented in a number of ways, with impacts that have clearly been exacerbated by climate change, there was one piece of the puzzle that didn't quite fit. Yes, it was an active season as measured by the number of tropical cyclones (i.e. the named storm count)--nominally 18 (though that number could still rise, as discussed below). That places it among the top 11 seasonal totals historically going back to 1851. But the season was not as active as one might have expected.

Our team was among several groups that predicted an extremely active season, with named storm counts in the mid 20s to low 30s. These forecasts were driven by the favorable climate factors that were at play, i.e. record tropical Atlantic warmth and a transition underway from El Niño toward La Niña conditions. Both factors favor active Atlantic hurricane seasons, as they are associated with a thermodynamically favorable, low-shear environment that is conducive to tropical cyclogenesis. Previous recent years with this combination of factors, 2005 and 2020, were associated with record numbers of named storms (28 and 30 respectively). With record warmth in the main development region ("MDR") for Atlantic tropical cyclones going into this year's season, our statistical modeling approach predicted between 27 and 39 storms, with a most likely estimate of 33 named storms.

That forecast however was contingent upon the development of a moderate La Niña during boreal autumn as models were predicting at the time. This did not come to pass, with current estimates showing neutral values of the "Nino3.4" index as of the El Niño phenomenon in late November. Our forecast in the alternative scenario of a neutral tropical Pacific state was instead for the slightly lower total of 25 – 36 storms, with a best guess of 30.5. The actual total of 18---as of the official end of the storm season--is clearly lower than the predicted range (we note here however that there is still a possibility that the final total will be 19 or even 20; during the 2005 season, for example, named storms continued on into January of the following year. Moreover, there is some subjectivity in the unofficial season total--if "potential cyclone eight" had been named by the National Hurricane Center, the total would already be 19. In some past years post-season analysis has added storms like this to the seasonal record, increasing the count total. That may well happen here). Nevertheless, the current count of 19 is roughly two standard errors below our mean forecast, which is almost certainly sufficient to declare our forecast "busted".

What might have gone wrong here? There are a couple confounding factors that are likely at work here. The hurricane season was unusually quiet during July and August when seasonal activity is typically ramping up. The season picked up considerably in September however. In fact, there were nearly as many named storms (13--or 14 if one includes "potential cyclone eight") during September-November as during the record-active years of 2005 and 2020 (16 named storms in both cases).

So there's no real discrepancy when it comes to the latter half of the season. It was basically as active as predicted. The puzzle is why July and August were so quiet despite clearly favorable seasonal large-scale climate conditions. This is where one runs into complications with intraseasonal variability. Of particular relevance is the so-called Madden-Julian oscillation or simply "MJO" to its friends. The MJO is a roughly 40-50 day oscillation in the tropical atmospheric circulation which influences the location of convection, which shifts east and west over the course of a single 40-50 day cycle. When the center of convection coincides with the tropical Atlantic, conditions are more favorable for tropical cyclogenesis. Conversely, if the center of convection shifts to e.g. the Pacific, conditions become unfavorable. This year, it happens that the unfavorable phase of the MJO coincided roughly with the peak of the storm season, inhibiting tropical cyclone formation at the very time it would typically be most prevalent. Secondarily, dry Saharan air outbreaks in July and August created unfavorable conditions for tropical cyclogenesis as well. The net effect was that unfavorable conditions related less to climate and more to just the vagaries of weather and intraseasonal variability conspired to make the 2024 storm season less active than it otherwise would have been. We should be thankful for that, given the devastating consequences of the storms that did form.

There is one other noteworthy detail here. Our group makes an alternative forecast in which tropical sea surface temperature (SST) in the main development region (MDR) is replaced with what we call "relative SST", defined as the difference between MDR SST and the average SST throughout the entire tropics, which some researchers have argued might be a better predictor of Atlantic hurricane activity. While our previous analyses have found that this alternative model yields less skillful predictions, it is notable that this year it yielded a much more accurate prediction of 19.9 +/- 4.5 total named storms that was remarkably close to the seasonal total.

So there are some interesting takeaways and a few conundrums to reflect upon as we look back at this unprecedented and unusual Atlantic hurricane season. With regard to our statistical model of Atlantic hurricane activity, it has generally yielded among the most accurate forecasts. In years where it's "missed" (i.e., the observed counts were outside the uncertainty range of the prediction), it has typically predicted too few storm counts. For example, in 2020, while we predicted the most active season of all forecasters (as many as 24 named storms), resulting from a similar combination of favorable factors that were observed heading into this season (i.e. very warm tropical Atlantic SSTs and a transition toward La Nina conditions), our prediction was too low--the actual count was a record 30 named storms. This is the first year where our prediction substantially exceeded the observed storm counts.

It's tempting to dismiss this as a one-off, i.e. the conspiring of unusual weather conditions at the height of the storm season, a bad roll of the dice. And that could be all it is. A more disturbing possibility is that the climate system is no longer behaving quite the way it used to, and some of the old rules and relationships no longer apply. Lest this sound like special pleading (and maybe it is), it is worth noting that respected colleagues of mine (climate scientists Gavin Schmidt and Zeke Hausfather) have argued precisely that in a recent New York Times op-ed entitled "We Study Climate Change. We Can’t Explain What We’re Seeing". Among other things, they argue that the progression of the latest El Niño episode simply doesn't match the pattern seen in past El Niño episodes. It is possible that climate change is altering the behavior of the phenomenon. And if that's the case, that it may also be altering the impact the phenomenon has on other attributes of the ocean-atmosphere system, including its influence on seasonal hurricane activity.

It's a disquieting possibility. And while in this case we're talking about impacts that were reduced relative to what had been predicted, there could well be far more unpleasant surprises in the greenhouse. It's unwise, in short, to tinker with a system you don't entirely understand. Particularly when our entire civilization is at stake.

Thread Information

Users Browsing this Thread

There are currently 1 users browsing this thread. (0 members and 1 guests)

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote