Post whatever black and white pictures you find interesting. You can post some back-ground info if you want, or not. Just a picture will do if you find it interesting. They don't have to be old, just black and white.

I got the idea after stumbling on this blog.

Interesting Black and White Photos from Past

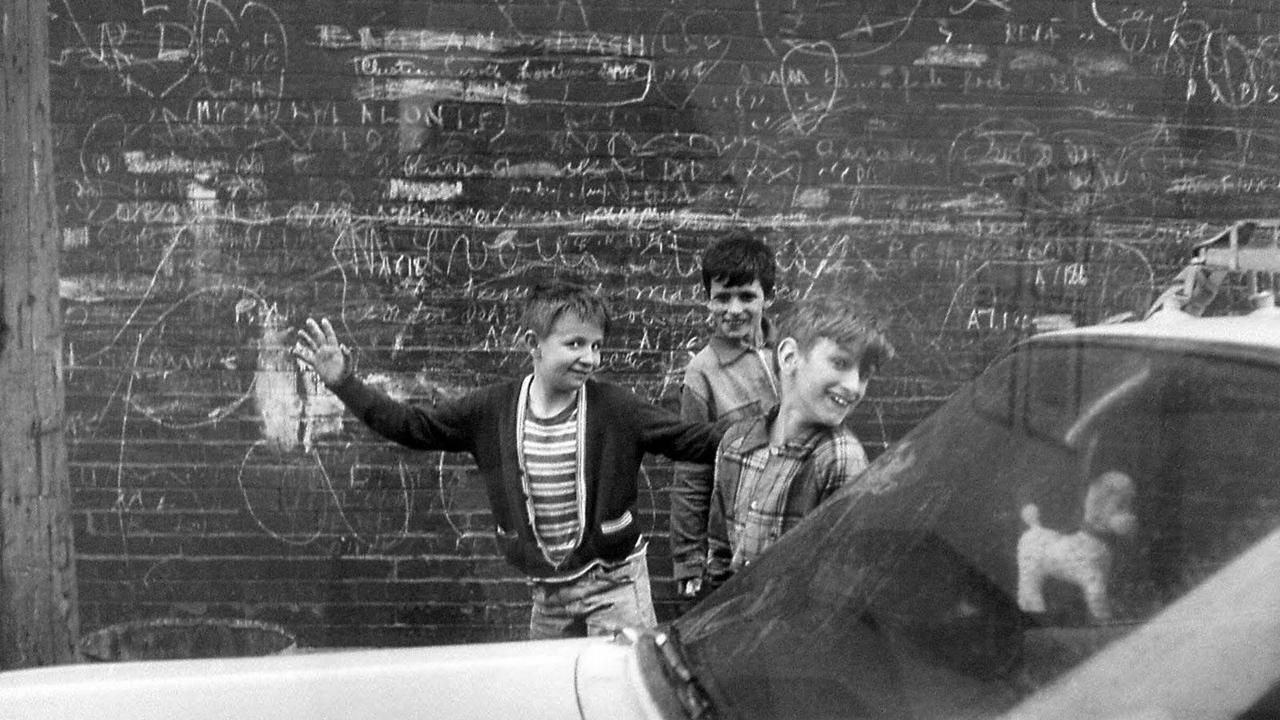

Helen Levitt - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Levitt grew up in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn, NY. She dropped out of high school and went to work for a commercial photographer. There, she taught herself photography. While teaching art classes to children in 1937, Levitt became intrigued with the transitory chalk drawings that were part of the New York children's street culture of the time. She purchased a Leica camera and began to photograph these works, as well as the children who made them. The resulting photographs were ultimately published in 1987 as In The Street: chalk drawings and messages, New York City 1938–1948.

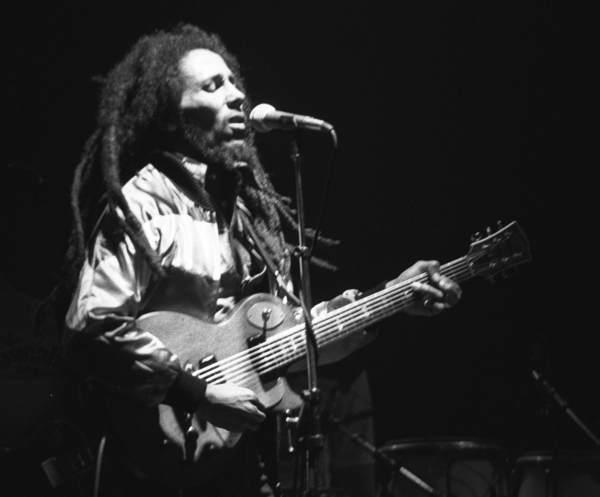

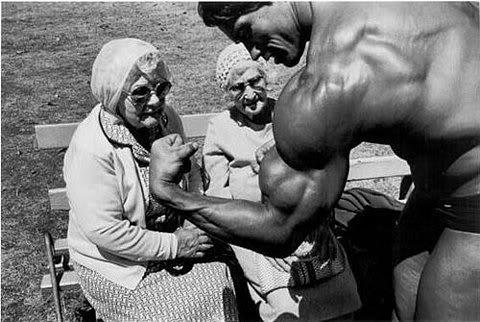

One for the King Willy of Indonesia.

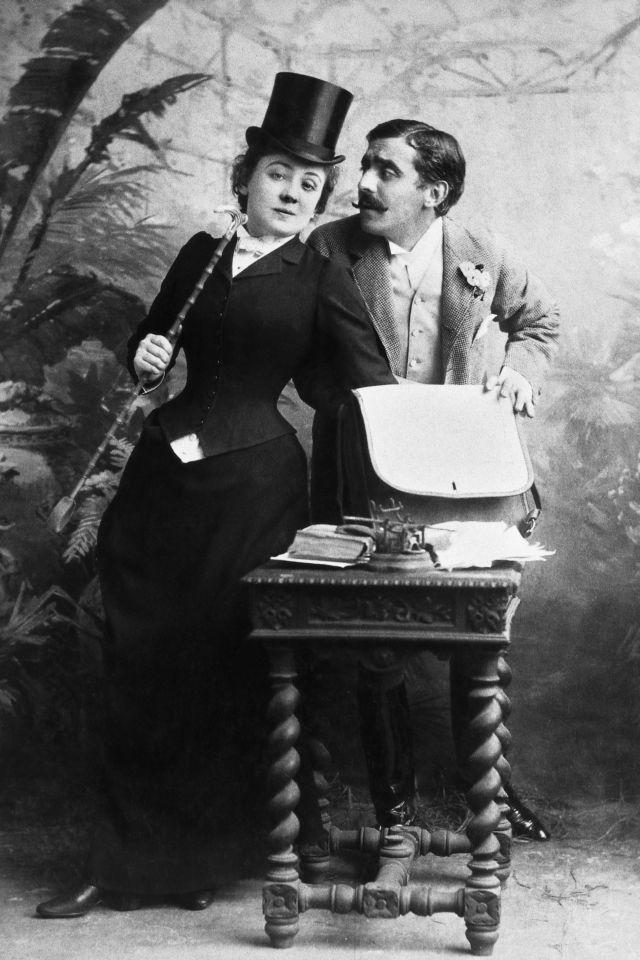

Arnold trying to grab a granny or two. The testosterone must have been giving him the horn something awful.

Looks like her hand is squeezing something in a bag judging by the expression on the blokes face.

Results 1 to 25 of 1318

-

03-03-2015, 08:39 PM #1

Interesting Black and White pictures ripped from the net

-

03-03-2015, 08:52 PM #2

^ The second picture isn't black and white.

-

03-03-2015, 09:07 PM #3

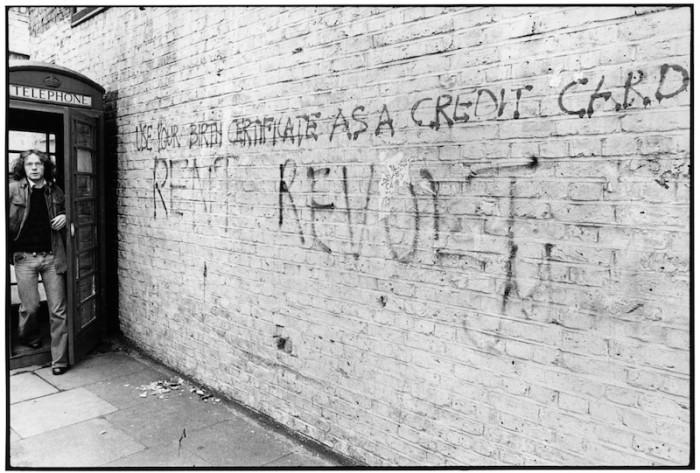

Nicked from here...All hail! The pioneers of British graffiti are marching! | Typorn.orgBlack diamonds? I shit 'em.

-

03-03-2015, 10:02 PM #4

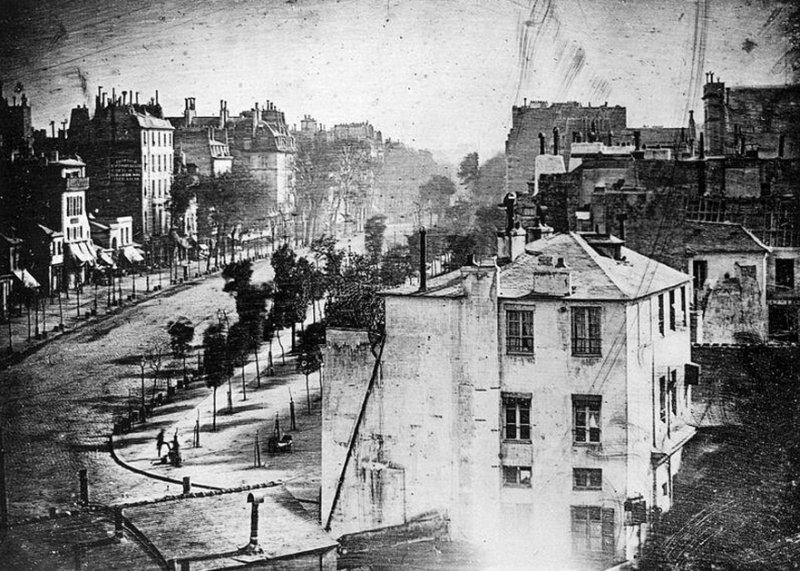

Apparently this is the oldest known photograph of people.

-

03-03-2015, 10:18 PM #5

^ Just read up about it.

It was quite accidental because the shoeshine boy and his customer were the only people to stay in position for the camera to capture.

-

03-03-2015, 10:33 PM #6

Good article about the picture below. Can't copy and paste the text. The website must have it disabled.

Great Photographs No.1 ? Boulevard du Temple, Paris, 8 in the morning

-

03-03-2015, 10:41 PM #7

^ Here is the text from the article...

It is a daguerrotype, taken by Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre (after whom the process was named), an image recorded on a sheet of copper coated with silver and developed by mercury fumes. Ironically the hour at which it was taken is known, but the year is not. It was either 1838 or 1839.

At first glance this may seem like a rather ordinary … even boring … subject. And it’s badly scratched too. Aren’t I saying its so great, simply because its so old?

No.

Look carefully to the bottom left. (You can click on the image to see it full-size.) There you will see two human figures, a customer having his shoes polished by a bootblack. These two unknown characters were the first humans to be photographed. Their simple, everyday transaction has made them immortal.

How come there is no one else in the image? Weren’t the streets of Paris busy at that time?

They were. But Daguerre would have had to use an exposure of 10-15 minutes to get this image. So all the other Parisians, bustling back and forth, have not have been recorded. Such was the length of exposure that anything in the frame for less that a few minutes would not register.

All the commentaries on this photograph that I have read speculate that these two were probably unaware that they were being recorded. And they say that Daguerre knew neither of them. One photo-historian writes, “He (Daguerre) quite possibly didn’t notice them as he focused his camera, but his plate remained true to nature, and one can imagine his delight when the mercury fumes revealed their presence during development.”

I wonder if that could be true.

Daguerre would have known that people moving about would not record on his plate and I have a sneaking suspicion he planted these two. Apart from anything else, who has one shoe polished for 10 to 15 minutes? Then it’s a slightly odd place for a bootblack to set up business, right on a corner, close to the kerb, and directly in the path of people walking up and down the road.

Finally, these two are very conveniently placed close to the classic compositional ‘thirds’ position.

I think that it has been set up … not that this detracts from the image in any way. Those two make the picture. I’m guessing that Daguerre knew a thing or two about composition as well as developing plates with mercury fumes. He knew that a ‘heartbeat’ would improve his image. But he couldn’t just have a person or two standing motionless on the street corner. Apart from the fact that it would look odd to passers-by, it would also look odd on the image. So, get them to do something, and what more natural than a shoe shine?

In a further bizarre twist of fate, we can still see and appreciate this image because of an invention of Daguerre’s great rival, William Henry Fox Talbot. Fox Talbot invented the calotype which was the precursor of modern film photography. (Film photography replaced the daguerrotype process and made it obsolete.)

Whilst this daguerrotype was display in a museum in Munich, in 1937, an eminent photo-historian, Beaumont Newhall commissioned a very high-quality photograph of it … using photographic film of course (i.e. based on Fox Talbot’s invention).

Subsequently, Daguerre’s picture survived the bombings of Munich in 1940 but, shortly after the war, an over-zealous museum curator attempted to clean it. The mercury amalgamated to the silver was incredibly fragile – likened to the powdery scales on a butterfly’s wings – and the hapless curator wiped the whole thing clean.

But Beaumont Newhall’s photograph of it survived. And a replica daguerrotype could be made.

An amazing story around a truly great photograph.

-

03-03-2015, 10:45 PM #8It is. Just turned sepia over the decades, as old pictures do. It was then scanned, not removing the color which is just fine.

Originally Posted by palexxxx

Originally Posted by palexxxx

-

03-03-2015, 10:59 PM #9RIP

- Join Date

- Nov 2013

- Last Online

- @

- Posts

- 16,939

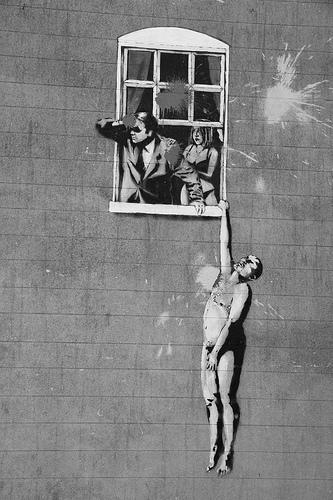

A few of my favs from a well known artist..

-

04-03-2015, 08:38 AM #10

Dorothea Lange's Migrant Mother depicts destitute pea pickers in California

-

04-03-2015, 09:22 AM #11

Margaret Thatcher and Garret Fitzgerald signing the Anglo-Irish agreement in 1985.

-

04-03-2015, 09:44 AM #12

-

04-03-2015, 09:50 AM #13

-

04-03-2015, 01:01 PM #14

This ward at the No 1 Australian Auxiliary Hospital in Middlesex, England, was decorated with a Santa Claus and a large map of Australia on the rear wall and the word "HOME" on it in large letters. However, it does not look as though the festivities have yet started.

In pictures: Eleven ways soldiers celebrated Christmas during World War I - ABC News (Australian Broadcasting Corporation)

StateLibQld 2 66852 Battle of Messines. Anzac Field Dressing Station scene 7 June, 1917

File:StateLibQld 2 66852 Battle of Messines. Anzac Field Dressing Station scene 7 June, 1917.jpg - Wikimedia Commons

-

04-03-2015, 03:57 PM #15The cold, wet one

- Join Date

- Aug 2007

- Last Online

- 31-03-2015 @ 03:06 PM

- Location

- In my happy place

- Posts

- 12,202

Not sure this'll work as I took it from facebook & if it does you'll have to click the link to see them, but these deserve to be shared...

40 Rare Historical Photographs You Must See

-

04-03-2015, 04:36 PM #16

Two of NRs linked photos. The others are worth looking at too.

Unknown Soldier In Vietnam, 1965

Sailor Kissing Nurse, Times Square, August 14, 1945

-

04-03-2015, 05:28 PM #17

-

05-03-2015, 03:17 PM #18

cliffs of moher George Karbus Photography

-

05-03-2015, 08:02 PM #19Thailand Expat

- Join Date

- Jun 2014

- Last Online

- @

- Posts

- 18,022

Don't forget to vote on a high rating for this thread, folks!

Should eventually be moved to classic if in sync with decent contributions.

-

05-03-2015, 11:04 PM #20

Photograph, b/w. Limerick Corporation fire brigade engine and crew outside the fire station at Roches Street, 1880 In pamphlet, Old Limerick, Treaty Press.

Limerick City Museum

-

06-03-2015, 01:34 AM #21The cold, wet one

- Join Date

- Aug 2007

- Last Online

- 31-03-2015 @ 03:06 PM

- Location

- In my happy place

- Posts

- 12,202

Maybe not interesting per se, but very glamorous

-

06-03-2015, 02:33 AM #22

^I really like the last one. Looks like a cheeky comment was passed. Nice pics.

-

06-03-2015, 02:35 AM #23

-

06-03-2015, 02:43 AM #24

Blacks During The Holocaust — Photograph

Nazi propaganda photo depicts friendship between an "Aryan" and a black woman. The caption states: "The result! A loss of racial pride." Germany, prewar.

— US Holocaust Memorial Museum

Blacks during the Holocaust — Photograph

I didn't know they had memes in the 70's.

-

06-03-2015, 10:03 AM #25

Thread Information

Users Browsing this Thread

There are currently 1 users browsing this thread. (0 members and 1 guests)

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote