NOAA – August 2023 was the warmest August recorded

Summer 2023 was the warmest Summer (JJA) recorded

Year-to-date (January – August) was the 2nd warmest January – August recorded

NOAA

_______

On September 10, 2023, sea ice in the Antarctic reached an annual maximum extent of 16.96 million square kilometers (6.55 million square miles), setting a record low maximum in the satellite record that began in 1979. This year’s maximum is 1.03 million square kilometers (398,000 square miles) below the previous record low set in 1986. It is also 1.75 million square kilometers below (676,000 square miles) below the 1981 to 2010 average Antarctic maximum extent. Sea ice extent is markedly below average north of Queen Maud Land and west of the Antarctic Peninsula. Other low areas include the Indian Ocean and Ross Sea. Extent is above average stretching out of the Amundsen Sea.

The Antarctic maximum extent is one of the earliest on record, having reached it 13 days earlier than the 1981 to 2010 median date of September 23. The interquartile range for the date of the Antarctic maximum is September 18 to September 30.

This year marks a significant record low maximum in Antarctic sea ice extent. Since early April 2023, sea ice maintained record low ice growth. From early to mid-August, growth slowed considerably, maintaining a difference of nearly 1.5 million square kilometers (579,000 square miles) between 2023 and 1986, the second lowest year on satellite record. After that period, ice growth quickened and narrowed the gap to about 1 million square kilometers (386,000 square miles). This is the first time that sea ice extent has not surpassed 17 million square kilometers (6.56 million square miles), falling more than one million square kilometers below the previous record low maximum extent set in 1986.

While weather conditions like winds and temperature control much of the day-to-day variations in ice extent, the long-term downward trend is a topic of much debate. The overall, trend in the maximum extent from 1979 to 2023 is 0.1 percent per decade relative to the 1981 to 2010 average, which is not a significant trend.

However, since August 2016, the Antarctic sea ice extent trend took a sharp downturn across nearly all months.

_______

Powerful space-based sensors and tools are monitoring deforestation around the world in close to real time, arming companies, nongovernmental organizations and governments with data to combat the growing problem.

Why it matters: Deforestation, which can contribute to climate change and habitat loss, is a particularly thorny problem to tackle on Earth because it typically happens in remote areas and is difficult to track from the ground.

- "These are huge areas, and we know that forests are critically important for mitigating climate change, for safeguarding biodiversity and also for local livelihoods in many cases," Mikaela Weisse, director of Global Forest Watch, tells Axios.

- Observing Earth from space makes tracking easier, giving those enforcing the laws on the ground strong evidence that illegal logging and other activities are occurring.

Driving the news: The company CTrees just launched a new portal called the Land Use Change Alert (LUCA) system that can inform users when deforestation and other "degradation" events are spotted globally using synthetic aperture radar, which cuts through cloud cover that has hampered other efforts at times.

- Right now, LUCA can alert users to these events on about a biweekly basis.

- Once the NISAR satellite — an Earth-observing mission from the U.S. and India — comes online next year, however, it should allow the tool to make alerts available in less than a week, Sassan Saatchi, co-founder and CEO of CTrees, tells Axios.

Zoom in: Big data analytics has also revolutionized how satellite data can be used to understand what's happening with forests on Earth.

- "In the past 10, 15 years, there has been a major shift in terms of our capability. We look at hundreds of terabytes of data in order to do this," Saatchi said.

- That analytical power has sped up processing times and made it easier to get more actionable information from huge amounts of data.

And getting that information into the hands of people on the ground quickly has been shown to help slow deforestation.

- A study from Global Forest Watch and others published in the Proceedings of the National Academies of Sciences in 2021 showed that Indigenous communities in Peru that used alerts powered by satellite data saw deforestation decrease by 52% in one year.

Between the lines: These types of systems can also be crucial for those trying to track and understand how the climate is changing.

- Forests are a major carbon sink, so when more trees are cut down, more of that carbon typically stored in these forests is released as greenhouse gases.

- "We need to quantify the carbon in a lot of forests globally, and we need to quantify how this carbon is changing and what are the drivers of the change. For any mitigation to really work, you need to know not only the quantity but also the ways that quantity changes and how you want to stop it," Saatchi said.

Yes, but: Having the data to understand when and where deforestation is happening is only part of the battle.

- Acting on it requires local governments and municipalities to have access to clear, understandable datasets, Weisse said.

- "We also do quite a bit of work with local and Indigenous communities as well either directly or through partners to train how those communities can benefit from this kind of data and in managing their lands," Weisse said.

What to watch: Other organizations are working to develop systems that would predict areas where deforestation might occur.

- The World Wide Fund for Nature and Deloitte are developing an advanced AI algorithm to figure out how likely deforestation is in any area based on geospatial data that tells researchers where deforestation is happening now, how easy it might be to transport logs and other factors, including the nearest palm oil processing mill.

_________

Swiss glaciers have lost 10% of their volume in just two years, a report has found.

Scientists have said climate breakdown caused by the burning of fossil fuels is the cause of unusually hot summers and winters with very low snow volume, which have caused the accelerating melts. The volume lost during the hot summers of 2022 and 2023 is the same as that lost between 1960 and 1990.

The analysis by the Swiss Academy of Sciences found 4% of Switzerland’s total glacier volume vanished this year, the second-biggest annual decline on record. The largest decline was in 2022, when there was a 6% drop, the biggest thaw since measurements began.

Experts have stopped measuring the ice on some glaciers as there is essentially none left. Glacier Monitoring in Switzerland (Glamos), which monitors 176 glaciers, recently halted measurements at the St Annafirn glacier in the central Swiss canton of Uri since it had mostly melted.

Matthias Huss, the head of Glamos, said: “We just had some dead ice left. It’s a combination of climate change that makes such extreme events more likely, and the very bad combination of meteorological extremes. If we continue at this rate … we will see every year such bad years.”

He said small glaciers were disappearing because of the rate of ice loss. In order to stop Switzerland losing its ice, emissions needed to be halted, he said, but added that even if the world managed to keep warming to 1.5C above preindustrial levels, only a third of glacier volume in Switzerland was forecast to remain.

This meant, he said, that “all the small glaciers will be gone anyway, and the big glaciers will be much smaller”. But he stressed that at least “there will be some ice in the highest regions of the Alps and some glaciers that we can show to our grandchildren”.

The Swiss Alps experienced record warmth this year. In August, the peak melt month, the Swiss weather service found that the elevation at which precipitation freezes hit a new record overnight high, measured 5,289 metres (17,350ft), an altitude higher than Mont Blanc. This exceeded last year’s record of 5,184 metres.

The mountain scenery is changing due to the melting ice. Huss has found new lakes forming next to glacier tongues for the first time on record, as well as bare rock poking from thinning ice. Bodies long lost under ice have been recovered as ice sheets have shrunk.

___________

A reminder

Ed Hawkins - Climate change is simple.

We started burning fossil fuels during the industrial revolution, adding extra carbon dioxide to the atmosphere.

As a direct consequence - due to well understood physics - global temperatures started to increase.

We are now experiencing the consequences.: https://twitter.com/ed_hawkins/statu...96288705212894

_______

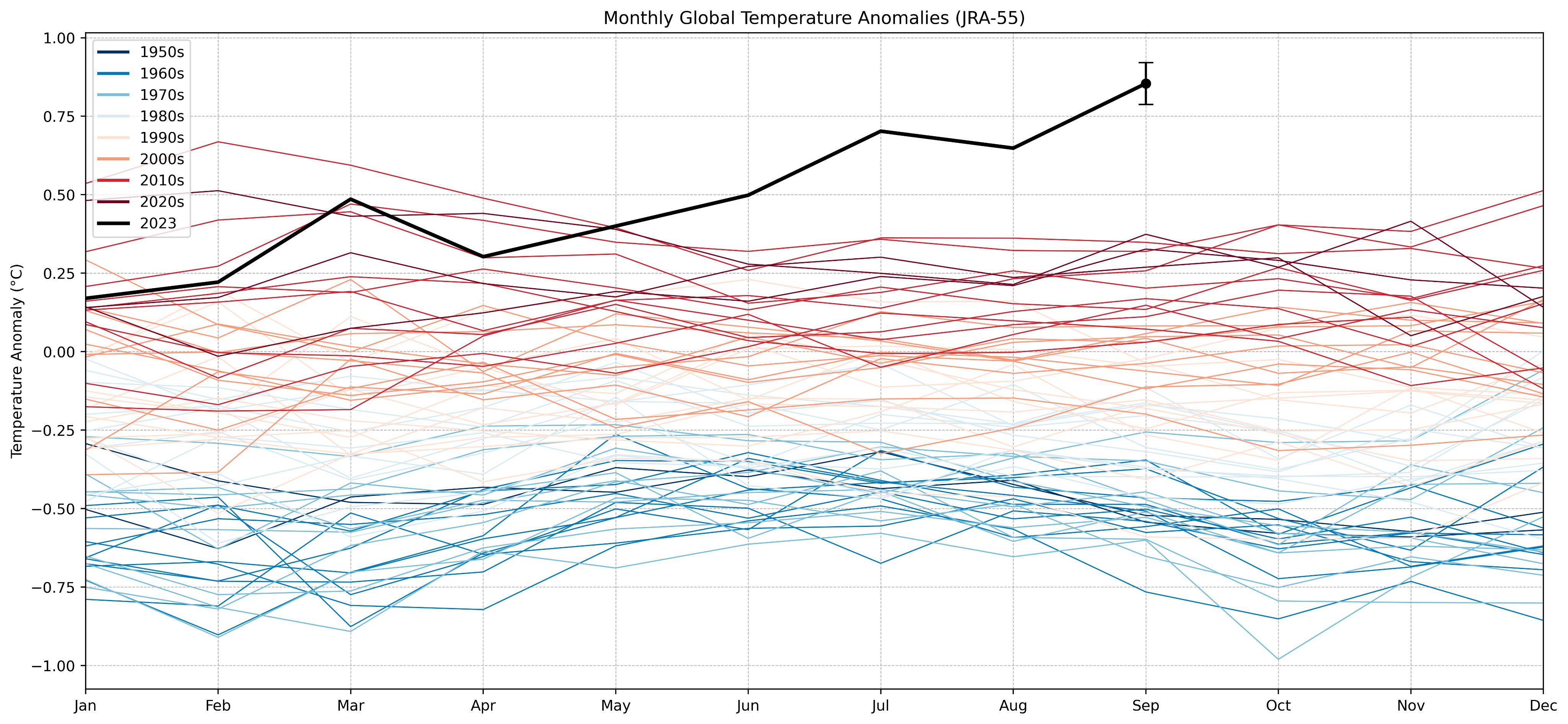

What September’s early numbers are showing.

Results 6,726 to 6,750 of 6805

Thread: Any doubts about Climate Change?

-

02-10-2023, 03:32 PM #6726

Last edited by S Landreth; 02-10-2023 at 06:17 PM.

Keep your friends close and your enemies closer.

-

02-10-2023, 05:22 PM #6727Thailand Expat

- Join Date

- Aug 2017

- Last Online

- Today @ 06:02 PM

- Location

- Sanur

- Posts

- 8,119

Why bother showing the period before the invention of the steam engine?

-

02-10-2023, 05:25 PM #6728

Because even you are entitled to feel nostalgic once in a while.

-

05-10-2023, 09:50 AM #6729

No need to panic, it will be cooler next year.

September 2023 was not only the hottest September on record, new data has confirmed today, but it was warmer by a margin described by stunned scientists as "extraordinary", "huge" and "whopping".

It keeps the world on course for its hottest year ever, expected to be 1.4C warmer than before the industrial era.

The new record is just the latest to be shattered this year, following a record hot June, July and summer overall, and record hot September in the UK.

Scientists are pointing the finger primarily at climate change, and warned of worse to come. But they also put it down to a warm weather pattern called El Nino, and natural changes in the weather.

September 2023 was world's hottest September on record by 'extraordinary' margin, new data confirms, with scientists blaming more than climate change | Climate News | Sky News

-

05-10-2023, 09:51 AM #6730

Two of the world’s few tropical glaciers, in Indonesia, are melting and their ice may vanish by 2026 or sooner as an El Niño weather pattern threatens to accelerate their demise, the country’s geophysics agency has said.

The agency, known as BMKG, has said the El Niño phenomenon could lead to the most severe dry season in Indonesia since 2019, increasing the risk of forest fires and threatening supplies of clean water.

El Niño also poses a threat to the Eternity Glaciers, which sit in the Jayawijaya mountains in the easternmost region of Papua and are melting at a rapid rate.

“The glaciers might vanish before 2026 or even faster, and El Niño could accelerate the melting process,” said Donaldi Permana, a climate researcher at the agency.

He said little could be done to prevent the shrinking, and the event could disrupt the regional ecosystem and cause a rise in the global sea level within a decade. We are now in a position to document the glaciers’ extinction,” Donaldi said. “At least we can tell future generations that we used to have glaciers.”

There are few such glaciers left in the tropics, and those that do remain are at risk. A study published in the journal Global and Planetary Change in 2021 tracked changes in the glaciers in Papua as well as in Kilimanjaro in Tanzania, the Andes in Peru and Bolivia, the Tibetan plateau and the Himalayas and found all were disappearing, with the loss of ice accelerating in recent years.

Glaciers in the tropics are especially vulnerable to climate change, surviving only because of their high altitudes. Researchers say precipitation that once fell as snow is now increasingly falling as rain, accelerating the melting of ice.

Donaldi said the Eternity Glaciers had thinned significantly in the past few years, from 32 metres in depth in 2010 to 8 metres in 2021, while their total width has contracted from 2.4km in 2000 to 230 metres in 2022.

Previous research by Donaldi and academics in the US found there was an intensification of ice loss near Puncak Jaya, or the Carstensz Pyramid, in Papua during the strong El Niño in 2015–16.

The combination of global heating and El Niño has already led to temperature records being broken globally over recent months, with the World Meteorological Organization declaring July the hottest month on record.

Indonesia is the world’s top exporter of coal, and aims to reach net zero emissions by 2060. Coal-fired power makes up more than half its energy supply. Last year it set an ambitious deadline of 2030 to cut emissions by 31.89% on its own, or by 43.2% with international support.

-

09-10-2023, 04:39 PM #6731

Copernicus – September 2023 was the warmest September record

Copernicus

__________

At least 43 million child displacements were linked to extreme weather events over the past six years, the equivalent of 20,000 children being forced to abandon their homes and school every single day, new research has found.

Floods and storms accounted for 95% of recorded child displacement between 2016 and 2021, according to the first-of-its-kind analysis by Unicef and the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC). The rest – more than 2 million children – were displaced by wildfires and drought.

Displacement is traumatic and frightening regardless of age, but the consequences can be especially disruptive and damaging for children who may miss out on education, life-saving vaccines and social networks.

“It is terrifying for any child when a ferocious wildfire, storm or flood barrels into their community,” said Unicef executive director Catherine Russell. “For those forced to flee, the fear and impact can be especially devastating, with worry of whether they will return home, resume school or be forced to move again.”

In absolute terms, China, the Philippines and India dominate with 22.3 million child displacements – just over half the total number – which the report attributes to the countries’ geographical exposure to extreme weather such as monsoon rains and cyclones and large child populations, as well as increased pre-emptive evacuations.

But the greatest proportion of child displacements were in small island states – many of which are facing existential threats due to the climate emergency – and in the Horn of Africa where conflict, extreme weather, poor governance and resource exploitation overlap.

A staggering 76% of children were displaced in the small Caribbean island of Dominica, which was devastated by Hurricane Maria in 2017, a category 4 Atlantic storm that damaged 90% of the island’s housing stock. Storms also led to more than a quarter of children being displaced in Cuba, Vanuatu, Saint Martin and the Northern Mariana Islands.

Somalia and South Sudan recorded the most child displacements due to floods, affecting 12% and 11% of the child population respectively.

Children Displaced in a Changing Climate is the first global analysis of the children driven from their homes due to floods, storms, droughts and wildfires, and comes as weather-related disasters are becoming more intense, destructive and unpredictable due to fossil-fuel driven global heating.

Skip

The Unicef analysis detected 1.3 million child displacements due to drought with Somalia, Ethiopia and Afghanistan by far the worst affected countries. Water scarcity forces people to move due to failed crops and to find drinking water for themselves and livestock, but the true scale of drought-migration is unknown as it is difficult to measure and radically underreported.

Meanwhile, the US accounted for three quarters (610,000 out of 810,000) of child displacements linked to wildfires, with over half of the rest happening in Canada, Israel, Turkey and Australia. In the US, fires are increasingly linked to the expanding wildland urban interface (WUI), the zone between undeveloped wildland and human development, where more than 3,000 homes and other buildings are lost annually.

Earlier this year, entire communities were displaced by wildfires in Canada and Greece.

Overall, children accounted for one in three of the 135 million global internal displacements that were linked to more than 8,000 weather-related disasters between 2016 and 2021 – and the toll is likely to get much worse, according to the report.

Riverine floods pose the biggest future risk and could displace almost 96 million children over the next 30 years, according to the IDMC disaster displacement model. Based on current climate data, winds and storm surge could displace 10.3 million and 7.2 million children respectively over the same period, though this could be much worse if fossil fuels are not phased out urgently.

Given their large populations, India, Bangladesh, Vietnam, the Philippines and China will likely have the most child displacements. In relative terms, children in the British Virgin Islands, the Bahamas, and Antigua and Barbuda are forecast to suffer most weather-disaster displacements over coming years.

“The figures are extremely worrying and demonstrate the urgent need for states to recognise and plan for the link between climate change and displacement, to minimize long term health, education and other developmental impacts on displaced children,” said Adeline Neau, an Amnesty International researcher for Central America and Mexico.

Children displaced in a changing climate | UNICEF

________

Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom signed two bills Saturday that would require large corporations operating in the state to disclose both their carbon footprints and their climate-related financial risks starting in 2026.

Background: SB 253, by Sen. Scott Wiener (D-San Francisco), and SB 261, from Sen. Henry Stern (D-Sherman Oaks), are the two most ambitious climate bills to come out of deep-blue California this year.

The laws faced heavy opposition from groups like the California Chamber of Commerce and the Western States Petroleum Association. Both authors amended their bills late in session to delay implementation and roll back corporate penalties for noncompliance. For SB 253 in particular, those amendments led companies like Google and Apple to support the bill and, ultimately, get enough Assembly Democrats on board to land it on Newsom’s desk.

Both bills failed in the Assembly last year.

Context: Taken together, the laws will change the landscape for corporate disclosure. For the first time in the U.S., large publicly traded and privately held corporations doing business in California will need to make public both their impact on the environment, including Scope 3 emissions or those generated through a company’s value chain, and how climate change is impacting their bottom line.

The laws go beyond proposed federal climate disclosure rules, which would only apply to publicly traded companies and wouldn’t mandate full Scope 3 disclosure.

What’s next: The laws will now be implemented by the California Air Resources Board, which needs to pass regulations by Jan. 1, 2025, before companies start filing disclosures in 2026.

Newsom has said he thinks the measures will need some “clean up.” CalChamber made similar comments on the need for additional legislation next year, but Wiener has warned that those industry efforts could signal a desire to “gut” SB 253 by removing the Scope 3 reporting requirement.

-

15-10-2023, 04:44 PM #6732

- Berkeley Earth - September 2023 was the warmest September recorded

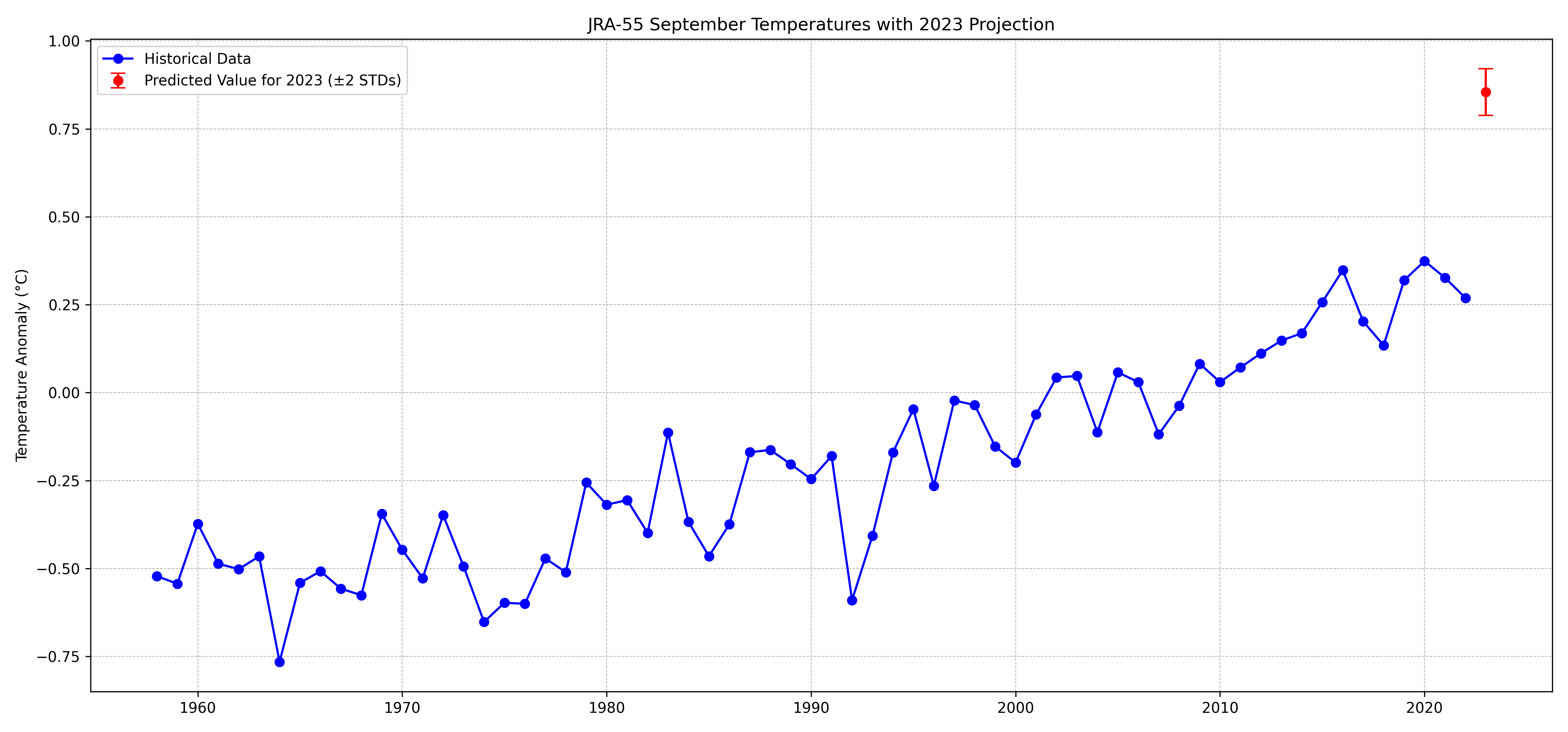

September also contained the annual maximum in Antarctic sea ice. It was by far the lowest maximum for sea ice extent in the modern satellite record (since 1979), and also one of the earliest dates for the peak to be observed.

Rest of 2023 - The statistical approach that we use, looking at conditions in recent months, now believes that 2023 is virtually certain to become the warmest year on record (>99% chance).

__________

The damage caused by the climate crisis through extreme weather has cost $16m (£13m) an hour for the past 20 years, according to a new estimate.

Storms, floods, heatwaves and droughts have taken many lives and destroyed swathes of property in recent decades, with global heating making the events more frequent and intense. The study is the first to calculate a global figure for the increased costs directly attributable to human-caused global heating.

It found average costs of $140bn (£115bn) a year from 2000 to 2019, although the figure varies significantly from year to year. The latest data shows $280bn in costs in 2022. The researchers said lack of data, particularly in low-income countries, meant the figures were likely to be seriously underestimated. Additional climate costs, such as from crop yield declines and sea level rise, were also not included.

The researchers produced the estimates by combining data on how much global heating worsened extreme weather events with economic data on losses. The study also found that the number of people affected by extreme weather because of the climate crisis was 1.2 billion over two decades.

Two-thirds of the damage costs were due to the lives lost, while a third was due to property and other assets being destroyed. Storms, such as Hurricane Harvey and Cyclone Nargis, were responsible for two-thirds of the climate costs, with 16% from heatwaves and 10% from floods and droughts.

The researchers said their methods could be used to calculate how much funding was needed for a loss and damage fund established at the UN’s climate summit in 2022, which is intended to pay for the recovery from extreme weather disasters in poorer countries. It could also rapidly determine the specific climate cost of individual disasters, enabling faster delivery of funds.

“The headline number is $140bn a year and, first of all, that’s already a big number,” said Prof Ilan Noy, at the Victoria University of Wellington in New Zealand, who carried out the study with colleague Rebecca Newman. “Second, when you compare it to the standard quantification of the cost of climate change [using computer models], it seems those quantifications are underestimating the impact of climate change.”

Noy said there were a lot of extreme weather events for which there was no data on numbers of people killed or economic damage: “That indicates our headline number of $140bn is a significant understatement.” For example, he said, heatwave death data was only available in Europe. “We have no idea how many people died from heatwaves in all of sub-Saharan Africa.”

The study, published in the journal Nature Communications, took a different approach based on how climate change had exacerbated the extreme weather events. Hundreds of “attribution” studies have been done, calculating how much more frequent global heating made extreme weather events. This allows the fraction of the damages resulting from human-caused heating to be estimated.

The researchers applied these fractions to the damages recorded in the International Disaster Database, which compiles available data on all disasters in which 10 people died, or 100 were affected, or the country declared a state of emergency or requested international assistance.

The central estimate was an average climate cost of $140bn a year, with a range from $60bn to $230bn. These estimates are much higher than those from computer models, which are based on changes in average global temperature rather than on the extreme temperatures increasingly being seen in the world.

The years with the highest overall climate costs were 2003, when a heatwave struck Europe; 2008, when Cyclone Nargis hit Myanmar; and 2010, when drought hit Somalia and a heatwave hit Russia. Property damages were higher in 2005 and 2017 when hurricanes hit the US, where property values are high.

_________

The globe's pronounced and unexpected temperature spike during the past few months is provoking unease among some of the most level-headed climate scientists.

The big picture: September was the most unusually warm month in recorded history. This followed record heat in June and July — which was also the planet's hottest month — as well as August.

- Climate scientists point to several factors propelling the climate into uncharted territory. These include a strengthening El Niño in the tropical Pacific Ocean to an undersea volcanic eruption last year, which injected water vapor into the upper atmosphere.

- Other developments, such as changes in fuel mixtures for large marine vessels and weather patterns in the North Atlantic, are coming under scrutiny too.

Of note: Yet the largest factor at work is long-term, human-caused climate change from burning fossil fuels like coal and gas.

Yes, but: The climate scientists Axios spoke with for this story noted there may be some aspects of the recent record-shattering global heat that are not fully understood.

- This isn't reason for panic, however; but it does showcase that climate change involves surprises.

- And as the climate continues to warm, there may be even more consequential and unforeseen shocks down the road.

- "Future researchers will be writing dissertations trying to unpack the mix of factors that led us to blow away all prior records this year," Zeke Hausfather, climate lead at the payments company Stripe, told Axios.

Between the lines: The Pacific Ocean has seen a rapid swing from a cool, three-year-long La Niña phase into an El Niño, which features unusually mild ocean temperatures in the central and eastern tropical Pacific.

- That may be pushing global average surface temperatures higher at faster-than-usual rates.

- "Climate change comes on top of natural fluctuations in the climate system, and in a hotter-than-average world there will be hotter and cooler years," Kate Marvel, a senior climate scientist at Project Drawdown, told Axios.

- "The usual suspects — climate change plus El Niño — go a long way toward explaining the excess heat of this summer," Marvel said. She cautioned that other sources of internal variability may be at play too and historically have led to unexpected outcomes.

- "There is always the possibility that something is going on that we've missed, but the Earth system is a strange beast even when it's not being disturbed," Marvel said.

Zoom out: At the start of the calendar year, few climate experts expected it would be the planet's warmest on record. Yet that is now a virtual lock in nearly every data set, from NASA to the Copernicus Climate Change Service.

- Much of the planet's high fever is traceable to record warm oceans worldwide, a characteristic of 2023's climate imperiling sensitive marine ecosystems.

- Berkeley Earth, an independent temperature tracking group, pegs the odds that 2023 will have a global average surface temperature that is more than 1.5°C (2.7°F) above pre-industrial levels at 90%, up from just 55% one month ago, and 1% before the year began.

- This is a symbolic milestone, since it is the more ambitious target in the Paris Climate Agreement. However, the Paris text refers to an average over multiple decades, not a single year.

- "The fact that this forecast has shifted so greatly serves to underscore the [extraordinary] progression of the last few months, whose warmth has far exceeded expectations," Berkeley Earth's Robert Rohde wrote in an analysis published Wednesday.

What they're saying: Andrew Dessler, a climate scientist at Texas A&M University, said the "sudden jump" in temperatures during just a few months' time has been the biggest surprise.

- Because all of the human-caused responses act on longer and slower time scales, this would suggest some combination of internal, largely natural climate variability, together with climate change.

- "It may be some compound mode or something weirder," he said, noting that while the temperature uptick is not a completely unforeseen outcome in climate model simulations, they depict it as being highly unlikely.

- "I think this makes everybody in the climate science community uneasy."

- Gavin Schmidt is the director of NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies, which is slated to release its September temperature data on Friday. He expects the temperature departures from average to shrink each month as we head into winter in the Northern Hemisphere.

- Yet with the strong to very strong El Niño forecast to last into 2024, global average temperatures are likely to stay unusually high. Typically, global temperatures peak a few months after El Niño does.

The bottom line: "2023 will be the warmest year (something I gave a 10% probability to at the end of 2022), but I think 2024 will be warmer still," Schmidt said.

_________

- Study: Climate change to drive temperatures too hot for humans

Billions of people are at risk of temperatures exceeding survivability limits if global temperatures increase by 1°C (1.8°F) or more above current levels, a new study warns. Even young, healthy people could find it unbearably hot during part of the year, the study finds.

Driving the news: Regions in the Middle East and South Asia would "experience the brunt of deadly or intolerable conditions," researchers noted. Toward the higher end of warming scenarios, "potentially lethal combinations of heat and humidity could spread" to areas including U.S. Midwestern states.

Why it matters: The study, published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on Monday, finds that temperatures are increasing and heat waves are becoming "more frequent, intense, and longer-lasting due to climate change."

- Some areas are already exceeding the limits of the human body's tolerance for the combined impacts of heat, humidity, sun exposure and other factors, known as the wet bulb temperature.

- This year, the world has endured some of the hottest summer and early fall temperatures on record, with global average surface temperatures temporarily exceeding the Paris Agreement's temperature target of 1.5°C (2.7°F) compared to preindustrial levels multiple times in 2023.

Yes, but: The Paris Agreement's threshold isn't truly broken until that higher level is maintained for about 30 years.

- This study by scientists from Penn State and elsewhere warns this could occur if significant emissions cuts aren't made.

What they did: Researchers modeled temperature scenarios ranging from the Paris Agreement's target of 1.5°C of warming through 4°C and identified regions most at risk from rising heat and humidity for the study.

- Researchers adopted a wet bulb temperature threshold, beyond which humans have great difficulty surviving, and used a slightly lower wet bulb temperature than the oft-mentioned 35°C (95°F) — based on the notion that humans may be more sensitive to humid heat than previously thought.

What they found: The regions projected to be the worst affected in scenarios that reach upward to 2 °C are equatorial and Sahel regions of Africa and eastern China, per the study. Researchers note this is "a viable outcome by the end of the century, perhaps sooner, without drastic reductions in greenhouse gas emissions."

- "Continued warming above 3 °C and 4 °C, respectively, causes North and South America, as well as northern Australia, to experience extended periods of dangerous heat," per the study.

Zoom out: The study bolsters other recent research showing human survivability limits being challenged in some parts of the world at current or higher levels of warming. A separate study last year warned of the emergence of an "extreme heat belt" from Texas to Illinois.

- That hyperlocal analysis of current and future extreme heat events by the nonprofit First Street Foundation found the heat index in these areas could reach 125°F at least one day a year by 2053.

- Another study published in 2020 found that intolerable heat was already occurring in some parts of the world, including the Middle East, and has been increasing in frequency.

Of note: Preliminary data from the Copernicus Climate Change Service shows the global average surface temperature for June through August was the hottest on record, as studies show climate change boosted the deadly heat in the U.S. and Europe.

- One study found it would have been "virtually impossible" without it.

The bottom line: "In the future, moist heat extremes will lie outside the bounds of past human experience and beyond current heat mitigation strategies for billions of people," per the study.

- "While some physiological adaptation from the thresholds described here is possible, additional behavioral, cultural, and technical adaptation will be required to maintain healthy lifestyles."

What they're saying: "This will be a critical benchmark for future studies," said atmospheric scientist Jane Baldwin of University of California Irvine who was not involved in the research, to Reuters.

- "Unfortunately, it's a somewhat grimmer picture than you would have gotten with the 35C limit."

________

Looking ahead……

Zeke Hausfather - Here are where we expect to see final October temperatures compared to all other Octobers in the dataset. This would likely end up somewhere around 1.5C to 1.7C above preindustrial levels: https://twitter.com/hausfath/status/1711409015929082164

Last edited by S Landreth; 15-10-2023 at 04:49 PM.

-

23-10-2023, 07:45 AM #6733

NASA – September 2023 was the warmest September recorded

Continuing the temperature trend from this summer, September 2023 was the hottest September on record, according to scientists at NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS). The month also set the record for the highest temperature anomaly – the largest difference from the long-term average.

This visualization shows global temperature anomalies along with the underlying seasonal cycle. Temperatures advance from January through December left to right, rising during warmer months and falling during cooler months. The color of each line represents the year, with colder purples for the 1960s and warmer oranges and yellows for more recent years. A long-term warming trend can be seen as the height of each month increases over time, the result of human activities releasing greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide into the atmosphere.

“What’s remarkable is that these record values are happening before the peak of the current El Nino event, whereas in 2016 the previous record values happened in the spring, after the peak,” said Gavin Schmidt, director of GISS. El Nino is the warm phase of a naturally recurring pattern of trade winds and ocean temperatures in the Eastern Tropical Pacific that influences global temperatures and precipitation patterns.

NASA

_________

Dr. Hausfather is the climate research lead at the payments company Stripe and a research scientist at Berkeley Earth, an independent organization that analyzes environmental data.

Staggering. Unnerving. Mind-boggling. Absolutely gobsmackingly bananas.

As global temperatures shattered records and reached dangerous new highs over and over the past few months, my climate scientist colleagues and I have just about run out of adjectives to describe what we have seen. Data from Berkeley Earth released on Wednesday shows that September was an astounding 0.5 degree Celsius (almost a full degree Fahrenheit) hotter than the prior record, and July and August were around 0.3 degree Celsius (0.5 degree Fahrenheit) hotter. 2023 is almost certain to be the hottest year since reliable global records began in the mid-1800s and probably for the past 2,000 years (and well before that).

While natural weather patterns, including a growing El Niño event, are playing an important role, the record global temperatures we have experienced this year could not have occurred without the approximately 1.3 degrees Celsius (2.3 degrees Fahrenheit) of warming to date from human sources of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gas emissions. And while many experts have been cautious about acknowledging it, there is increasing evidence that global warming has accelerated over the past 15 years rather than continued at a gradual, steady pace. That acceleration means that the effects of climate change we are already seeing — extreme heat waves, wildfires, rainfall and sea level rise — will only grow more severe in the coming years.

I don’t make this claim lightly. Among my colleagues in climate science, there are sharp divisions on this question, and some aren’t convinced it’s happening. Climate scientists generally focus on longer-term changes over decades rather than year-to-year variability, and some of my peers in the field have expressed concerns about overinterpreting short-term events like the extremes we’ve seen this year. In the past I doubted acceleration was happening, in part because of a long debate about whether global warming had paused from 1998 to 2012. In hindsight, that was clearly not the case. I’m worried that if we don’t pay attention today, we’ll miss what are increasingly clear signals.

Global warming may have accelerated in the past 15 years

Annual average temperatures since 1850

I wouldn’t be making this argument if I didn’t have strong evidence to back it up; the data we’re getting from three sources tells a worrying story about a world warming more quickly than before. First, the rate of warming we’ve measured over the world’s land and oceans over the past 15 years has been 40 percent higher than the rate since the 1970s, with the past nine years being the nine warmest years on record. Second, there has been acceleration over the past few decades in the total heat content of Earth’s oceans, where over 90 percent of the energy trapped by greenhouse gases in the atmosphere is accumulating. Third, satellite measurements of Earth’s energy imbalance — the difference between energy entering the atmosphere from the sun and the amount of heat leaving — show a strong increase in the amount of heat trapped over the past two decades. If Earth’s energy imbalance is increasing over time, it should drive an increase in the world’s rate of warming.

There are a number of factors driving the acceleration of warming. While the world has made real progress in slowing down the growth of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gas emissions, they have yet to peak and decline. And on top of this, we are reaping the results of what the climate scientist James Hansen calls our “Faustian bargain” with air pollution. For decades, air pollution from sulfur dioxide and other hazardous substances in fossil fuels has had a strong temporary cooling effect on our climate. But as countries around the world have begun to clean up the air, the cooling effect provided by these aerosols has fallen by around 30 percent since 2000. Aerosols have fallen even more in the past three years, after a decision to largely phase out sulfur in marine fuels in 2020. These reductions in pollution on top of continued increases in atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations mean that we are encountering some of the unvarnished force of climate change for the first time.

Until recently, climate change was framed as an issue that would affect our children. Today it is nearly omnipresent, and it is impossible to ignore. And very soon, with the acceleration, we will experience even more of its effects: Ice sheets and glaciers will melt faster, extreme weather events will become more frequent, and even more plants and animals will be put at risk of extinction.

Does this acceleration mean that warming is happening faster than we thought or that it is too late to avoid the worst impacts? Not necessarily. Amazingly enough, this acceleration quite closely matches what climate models have projected for this period. In other words, scientists have long foreseen a possible acceleration of warming if our aerosol emissions declined while our greenhouse gas emissions did not. That’s what we’re now seeing. This may not make you feel much better about the future of warming but should at least make you feel better about our models and the power of science to prepare us for what’s to come.

It’s now clear that we can control how warm the planet gets over the coming decades. Climate models have consistently found that once we get emissions down to net zero, the world will largely stop warming; there is no warming that is inevitable or in the pipeline after that point. Of course, the world will not cool back down for many centuries, unless world powers join in major efforts to remove more carbon dioxide from the atmosphere than we add. But that is the brutal math of climate change and the reason we need to speed up efforts to reduce emissions significantly.

On that front, there is some reason for cautious hope. The world is on the brink of a clean energy transition. The International Energy Agency recently estimated that a whopping $1.8 trillion will be invested in clean energy technologies like renewables, electric cars and heat pumps in 2023, up from roughly $300 billion a decade ago. Prices of solar, wind and batteries have plummeted over the past 15 years, and for much of the world, solar power is now the cheapest form of electricity. If we reduce emissions quickly, we can switch from a world in which warming is accelerating to one in which it’s slowing. Eventually, we can stop it entirely.

We are far from on track to meet our climate goals, and much more work remains. But the positive steps we’ve made over the past decade should reinforce to us that progress is possible and despair is counterproductive. Despite the recent acceleration of warming, humans remain firmly in the driver’s seat, and the future of our climate is still up to us to decide.

_________

- Zack Labe - The size of the global sea ice departure (i.e., amount of missing ice compared to 1981-2010) has just reached the largest anomaly in our satellite record...

https://twitter.com/ZLabe/status/1713905827684450415

_______

While the Southern Ocean around Antarctica has been warming for decades, the annual extent of winter sea ice seemed relatively stable — compared to the Arctic. In some areas Antarctic sea ice was even increasing.

That was until 2016, when everything changed. The annual extent of winter sea ice stopped increasing. Now we have had two years of record lows.

In 2018 the international scientific community agreed to produce the first marine ecosystem assessment for the Southern Ocean. We modelled the assessment process on a working group of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). So the resulting “summary for policymakers” being released today is like an IPCC report for the Southern Ocean.

This report can now be used to guide decision-making for the protection and conservation of this vital region and the diversity of life it contains.

Why should we care about sea ice?

Sea ice is to life in the Southern Ocean as soil is to a forest. It is the foundation for Antarctic marine ecosystems.

Less sea ice is a danger to all wildlife — from krill to emperor penguins and whales.

The sea ice zone provides essential food and safe-keeping to young Antarctic krill and small fish and seeds the expansive growth of phytoplankton in spring, nourishing the entire food web. It is a platform upon which penguins breed, seals rest and around which whales feed.

The international bodies that manage Antarctica and the Southern Ocean under the Antarctic Treaty System urgently need better information on marine ecosystems. Our report helps fill this gap by systematically identifying options for managers to maximise the resilience of Southern Ocean ecosystems in a changing world.

An open and collaborative process

We sought input from a wide range of people across the entire Southern Ocean science community.

We sought to answer questions about the state of the whole Southern Ocean system - with an eye on the past, present and future.

Our team comprised 205 authors from 19 countries. They authored 24 peer-reviewed papers. We then distilled the findings from these papers into our summmary for policymakers.

We deliberately modelled the multi-disciplinary assessment process on a working group of the IPCC to distill the science into an easy-to-read and concise narrative for politicians and the general public alike. It provides a community assessment of levels of certainty around what we know.

We hope this “sea change” summary sets a new benchmark for translating marine research into policy responses.

So what’s in the report?

Southern Ocean habitats, from the ice at the surface to the bottom of the deep sea, are changing. The warming of the ocean, decline in sea ice, melting of glaciers, collapse of ice shelves, changes in acidity and direct human activities such as fishing, are all impacting different parts of the ocean and their inhabitants.

These organisms, from microscopic plants to whales, face a changing and challenging future. Important foundation species such as Antarctic krill are likely to decline with consequences for the whole ecosystem.

The assessment stresses climate change is the most significant driver of species and ecosystem change in the Southern Ocean and coastal Antarctica. It calls for urgent action to curb global heating and ocean acidification.

It reveals an urgent need for international investment in sustained, year-round and ocean-wide scientific assessment and observations of the health of the ocean.

We also need to develop better integrated models of how individual changes in species along with human impacts will translate to system-level change in the different food webs, communities and species.

________

Looking at year end

- Gavin Schmidt - With the huge September data in, we can confirm that we expect 2023 to be the warmest year in the record (99% probability).: https://twitter.com/ClimateOfGavin/s...93305099370893

-

30-10-2023, 04:49 PM #6734

NOAA – September 2023 was the warmest September recorded

Year-to-date, January – September 2023 was the warmest recorded

NOAA

___________

Accelerated ice melt in west Antarctica is inevitable for the rest of the century no matter how much carbon emissions are cut, research indicates. The implications for sea level rise are “dire”, scientists say, and mean some coastal cities may have to be abandoned.

The ice sheet of west Antarctica would push up the oceans by 5 metres if lost completely. Previous studies have suggested it is doomed to collapse over the course of centuries, but the new study shows that even drastic emissions cuts in the coming decades will not slow the melting.

The analysis shows the rate of melting of the floating ice shelves in the Amundsen Sea will be three times faster this century compared with the previous century, even if the world meets the most ambitious Paris agreement target of keeping global heating below 1.5C above pre-industrial levels.

Losing the floating ice shelves means the glacial ice sheets on land are freed to slide more rapidly into the ocean. Many millions of people live in coastal cities that are vulnerable to sea level rise, from New York to Mumbai to Shanghai, and more than a third of the global population lives within 62 miles (100km) of the coast.

The climate crisis is driving sea level rise by the melting of ice sheets and glaciers and the thermal expansion of sea water. The biggest uncertainty in future sea level rise is what will happen in Antarctica, the scientists say, making planning to adapt to the rise very hard. Researchers said translation of the new findings on ice melting into specific estimates of sea level rise was urgently needed.

“Our study is not great news – we may have lost control of west Antarctic ice shelf melting over the 21st century,” said Dr Kaitlin Naughten, at the British Antarctic Survey, who led the work. “It is one impact of climate change that we are probably just going to have to adapt to, and very likely this means some coastal communities will either have to build [defences] or be abandoned.”

Naughten said her research showed the situation was more perilous than previously thought. “But we shouldn’t give up [on climate action] because even if this particular impact is unavoidable, it is only one impact of climate change,” she added. “Our actions likely will make a difference [to Antarctic ice melting] in the 22nd century and beyond, but that’s a timescale that probably none of us today will be around to see.”

The research, published in the journal Nature Climate Change, used a high-resolution computer model of the Amundsen Sea to provide the most comprehensive assessment of warming in the region to date. The results indicated that increased rates of melting in the 21st century were inevitable in all plausible scenarios for the pace of cuts in fossil fuel burning.

Unavoidable future increase in West Antarctic ice-shelf melting over the twenty-first century | Nature Climate Change

________

Climate change-driven disasters have caused damages equivalent to $391 million a day for 20 years, according to projections published in the journal Nature Communications.

Researchers determined that between 2000 and 2019, climate disasters such as droughts and heatwaves did about $143 billion of damage annually. They attributed 63 percent of those damages — $90 billion — to loss of human lives, and the remainder predominantly to property damage.

Researchers noted that the projections also fail to capture indirect impacts that “may be significant.” As an example, they cited the impacts of air pollution in the northeastern U.S. from Canada’s 2023 wildfires, although those occurred outside the research’s date range. Their methodology cannot “account for these indirect losses, even though these could conceivably be orders of magnitude larger than the original damage wrought by these events (and were likely much larger in this specific case),” researchers wrote.

On a year-by-year basis, the highest costs from climate change were in 2008, when researchers put costs at $620 billion. Other high points occurred in 2003 and 2010. These peaks, the researchers noted, were driven by particularly high-casualty climate events in those years. For example, 2008 saw Tropical Cyclone Nargis in Myanmar, which killed an estimated 84,537 people, while in 2003, a European heatwave caused an estimated 70,000 deaths.

Excluding loss of life from the equation changes the years when damages peaked. Under this formula, the peaks were in 2005, when Hurricanes Katrina, Rita and Wilma did $123 billion in financial damages, and 2017, when Hurricanes Harvey, Irma and Maria did $139 billion in damages. Notably, all of these storms hit the United States, suggesting that while the U.S. has suffered some of the most expensive climate disasters, the deadliest occurred elsewhere.

The date range for the research ends before 2023, which saw the hottest summer ever recorded. Recent years have also seen further heatwaves in Europe, as well as similar extreme heat in the Pacific Northwest, which, like Europe, is not acclimated to such temperatures, meaning numerous residents do not have air conditioning.

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-023-41888-1#Sec8

________

Family doctors in Canada, physicians in Brazil, GPs in Australia – and many other countries – joined forces at the WONCA World Conference to make an urgent call for governments to combat the growing health impact of climate change.

Gathering in front of media for ‘Green Day’, they voiced their support of an open letter with 40 signatories, including the RACGP, asking politicians to do more to protect their citizens from the health impacts of the crisis.

Speaking in front of a large international group of doctors who had donned green clothing in support of the message, RACGP Specific Interests Climate and Environmental Medicine Chair Dr Catherine Pendrey said that many attendees have directly treated patients impacted by climate change.

‘From the Black Summer bushfires to the Lismore floods, general practitioners and family doctors are on the front line of supporting their communities from climate change and its health impacts,’ she told reporters.

This is the reason health organisations representing three million health professionals have raised their concerns, according to Dr Pendrey.

The letter comes in the wake of new reports suggesting the Earth has seen the highest temperatures recorded for 100,000 years, while freak natural disasters have impacted millions, including record-breaking wildfires in Canada and the Amazon, unusual flooding in China, the Mediterranean and Australia’s east coast, and above average hurricane activity in the Atlantic.

It requests governments to take the following actions at the UN Climate Change Conference (COP 28), which takes place from 30 November to 12 December:

- Halt any expansion of new fossil fuel infrastructure and production

- Phase out existing production and use of fossil fuels

- Remove fossil fuel subsidies

- Increase investment in renewable energy

- Fast-track a just transition away from fossil fuel energy systems

-

06-11-2023, 07:29 AM #6735

JMA – September 2023 was the warmest September recorded

Five Warmest Years (Anomalies)

1st. 2023 (+0.75°C), 2nd. 2015 (+0.33°C), 3rd. 2016 (+0.32°C), 4th. 2019 (+0.31°C), 5th. 2021, 2020 (+0.30°C)

JMA

_________

End of year estimate….

Hottest year across all records

Based on the temperatures recorded over the first nine months of the year, current El Niño conditions and projected El Niño conditions over the remainder of the year, Carbon Brief can provide an estimate of where each different surface temperature record will likely end up.

The figure below shows both the prior record warmest year in each record (coloured square), as well as Carbon Brief’s central estimate of where 2023 will end up (coloured circle) and the 95th percentile confidence interval of that estimate.

_________

Looking ahead at October numbers

JMA and Copernicus have recorded October 2023 the warmest October recorded.

more later

_________

Having good chance of limiting global heating to 1.5C is gone, sending ‘dire’ message about the adequacy of climate action

The carbon budget remaining to limit the climate crisis to 1.5C of global heating is now “tiny”, according to an analysis, sending a “dire” message about the adequacy of climate action.

The carbon budget is the maximum amount of carbon emissions that can be released while restricting global temperature rise to the limits of the Paris agreement. The new figure is half the size of the budget estimated in 2020 and would be exhausted in six years at current levels of emissions.

Temperature records have been obliterated in 2023, with extreme weather supercharged by global heating hitting lives and livelihoods across the world. At the imminent UN Cop28 climate summit in the United Arab Emirates there are likely to be disputes over calls for a phaseout of fossil fuels.

The analysis found the carbon budget remaining for a 50% chance of keeping global temperature rise below 1.5C is about 250bn tonnes. Global emissions are expected to reach a record high this year of about 40bn tonnes. To retain the 50% chance of a 1.5C limit, emissions would have to plunge to net zero by 2034, far faster than even the most radical scenarios.

The current UN ambition is to cut emissions by half by 2030 and reach net zero by 2050, although existing policies are far from delivering this ambition. If it was achieved, however, it would mean only about a 40% chance of staying below 1.5C, the scientists said, so breaking the limit would be more likely than not.

But, they warned, every 10th of a degree of extra heat caused more human suffering and therefore keeping as close as possible to 1.5C was crucial.

The new carbon budget estimate is the most recent and comprehensive analysis to date. The main reasons the budget has shrunk so markedly since 2020 are the continued high emissions from human activities and a better understanding of how reducing air pollution increases heating by blocking less sunlight.

Prof Joeri Rogelj, at Imperial College London, UK, and one the study’s authors, said: “The budget is so small, and the urgency of meaningful action for limiting warming is so high, [that] the message from [the carbon budget] is dire.

“Having a 50% or higher likelihood that we limit warming to 1.5C is out of the window, irrespective of how much political action and policy action there is.” He said it was “remarkable” how much risk humanity appeared willing to take with global heating.

Dr Chris Smith, at the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis in Austria, who was also part of the study, said: “Governments can control the emissions but, at the moment, they have not done so. This is why we have an ever-shrinking carbon budget. We are not saying we only have six years to solve climate change – absolutely not. If we are able to limit warming to 1.6C or 1.7C, that’s a lot better than 2C. We still need to fight for every 10th of a degree.”

The study, published in the journal Nature Climate Change, used updated data and improved climate modelling compared with other recent estimates. It also used the latest figures showing that aerosol air pollution and the clouds it was helping to seed were better at blocking sunlight and limiting heating than previously thought. As a result, lower pollution in future would mean more global heating and therefore a smaller carbon emissions budget to remain under 1.5C.

The analysis also looked at the 2C upper limit in the Paris agreement, which even if met would still mean a sharp increase in climate impacts from heatwaves to floods to crop losses.

For a 90% chance of keeping below 2C, emissions would have to hit net zero in about 2035, the study found. Achieving net zero in 2050 would give a 66% chance of meeting the 2C target.

Assessing the size and uncertainty of remaining carbon budgets | Nature Climate Change

_________

Global heating is accelerating faster than is currently understood and will result in a key temperature threshold being breached as soon as this decade, according to research led by James Hansen, the US scientist who first alerted the world to the greenhouse effect.

The Earth’s climate is more sensitive to human-caused changes than scientists have realized until now, meaning that a “dangerous” burst of heating will be unleashed that will push the world to be 1.5C hotter than it was, on average, in pre-industrial times within the 2020s and 2C hotter by 2050, the paper published on Thursday predicts.

This alarming speed-up of global heating, which would mean the world breaches the internationally agreed 1.5C threshold set out in the Paris climate agreement far sooner than expected, risks a world “less tolerable to humanity, with greater climate extremes”, according to the study led by Hansen, the former Nasa scientist who issued a foundational warning about climate change to the US Congress back in the 1980s.

Hansen said there is a huge amount of global heating “in the pipeline” because of the continued burning of fossil fuels and Earth being “very sensitive” to the impacts of this – far more sensitive than the best estimates laid out by the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

“We would be damned fools and bad scientists if we didn’t expect an acceleration of global warming,” Hansen said. “We are beginning to suffer the effect of our Faustian bargain. That is why the rate of global warming is accelerating.”

The question of whether the rate of global heating is accelerating has been keenly debated among scientists this year amid months of record-breaking temperatures.

Hansen points to an imbalance between the energy coming in from the sun versus outgoing energy from the Earth that has “notably increased”, almost doubling over the past decade. This ramp-up, he cautioned, could result in disastrous sea level rise for the world’s coastal cities.

The new research, comprising peer-reviewed work of Hansen and more than a dozen other scientists, argues that this imbalance, the Earth’s greater climate sensitivity and a reduction in pollution from shipping, which has cut the amount of airborne sulphur particles that reflect incoming sunlight, are causing an escalation in global heating.

“We are in the early phase of a climate emergency,” the paper warns. “Such acceleration is dangerous in a climate system that is already far out of equilibrium. Reversing the trend is essential – we must cool the planet – for the sake of preserving shorelines and saving the world’s coastal cities.”

To deal with this crisis, Hansen and his colleagues advocate for a global carbon tax as well as, more controversially, efforts to intentionally spray sulphur into the atmosphere in order to deflect heat away from the planet and artificially lower the world’s temperature.

So-called “solar geoengineering” has been widely criticized for threatening potential knock-on harm to the environment, as well as over the risks of a whiplash heating effect should the injections of sulphur cease, but is backed by a minority of scientists who warn that the world is running out of time and options to avoid catastrophic temperature growth.

Hansen said that while cutting emissions should be the highest priority, “thanks to the slowness in developing adequate carbon-free energies and failure to put a price on carbon emissions, it is now unlikely that we can get there – a bright future for young people – from here without temporary help from solar radiation management”.

This year is almost certain to be the hottest ever reliably recorded, with temperatures in September described as “gobsmackingly bananas” by one climate researcher. A report this week found that the carbon budget to limit the world to 1.5C of heating is now nearly exhausted due to the continued burning of fossil fuels and deforestation.

-

08-11-2023, 11:46 AM #6736

Copernicus – October 2023 was the warmest October recorded

Year to date

https://www.copernicus.eu/en

-

08-11-2023, 12:57 PM #6737Thailand Expat

- Join Date

- Jan 2006

- Last Online

- 23-01-2024 @ 08:31 AM

- Location

- Upper N.East

- Posts

- 2,081

WHY ARE THESE CLIMATE HORROR STORIES SOOOO LONG WINDED? They are scare tactics headlines...never intended for people to actually read. Really just political messages presented in a compelling manner as expected for belief but untrue.

-

08-11-2023, 01:14 PM #6738

-

13-11-2023, 07:10 AM #6739

- Last 12 months were hottest ever recorded: Report

The last 12 months were the hottest ever recorded, with an estimated 7.8 billion people around the world experiencing above-average warmth, according to a new analysis from Climate Central.

The report, published Wednesday, analyzed temperatures between November 2022 and October 2023 and found global warming surpassed 1.3 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, setting a new 12-month record.

Over the 12 months, the mean temperatures in 170 countries exceeded 30-year norms, meaning 99 percent of humanity experienced above-average warmth, Climate Central said.

Only Iceland and Lesotho experienced cooler-than-normal temperatures, according to the report.

Researchers found about 5.7 billion people from several countries — including Japan, Indonesia, the United Kingdom and Brazil — were exposed to at least 30 days of above-average temperatures during the 12-month span. Using Climate Central’s temperature attribution system, the nonprofit found that these temperatures were made at least three times more likely by the influence of climate change.

Across 200 cities, more than 500 million people experienced streaks of extreme heat, defined by the report as at least five days of daily temperatures in the 99th percentile when compared to the 30-year norms.

Houston experienced the most extreme heat, with 22 consecutive days between July 31 and Aug. 21, while New Orleans and the Indonesian cities of Jakarta and Tangerang had 17 straight days of extreme heat.

In Texas, Austin, San Antonio and Dallas were among the cities with the longest extreme heat streaks. In those cities, Climate Central found climate change made this extreme heat at least five times more likely.

__________

Extreme droughts that have wrecked the lives of millions of people in Syria, Iraq and Iran since 2020 would not have happened without human-caused global heating, a study has found.

The climate crisis means such long-lasting and severe droughts are no longer rare, the analysis showed. In the Tigris-Euphrates basin, which covers large parts of Syria and Iraq, droughts of this severity happened about once every 250 years before global heating – now they are expected once a decade.

In Iran, extreme drought occurred once every 80 years in the past but now strikes every five years on average in today’s hotter world. Further global heating, driven by the burning of fossil fuels, will make these droughts even more common.

The study also found that existing vulnerability from years of war and political instability had reduced people’s ability to cope with the drought, turning it into a humanitarian disaster.

The researchers said it was vital to plan for more frequent droughts in the future.

“Our study has shown that human-caused climate change is already making life considerably harder for tens of millions of people in west Asia,” said Prof Mohammad Rahimi, at Semnan University, Iran. “And with further warming, Syria, Iraq and Iran will become even harsher places to live.”

Rana El Hajj, at the Red Cross Red Crescent climate centre, said: “While conflict itself increases vulnerability to drought by contributing to land degradation, weakened water management and deteriorating infrastructure, research also shows that climate change, in this region specifically, has acted as a threat multiplier [for conflict].”

Dr Friederike Otto, at Imperial College London, UK, said: “Droughts like this will continue to intensify until we stop burning fossil fuels. If the world does not agree to phase out fossil fuels at [UN climate summit] Cop28, everyone loses: more people will suffer from water shortages, more farmers will be displaced and many people will pay more for food at supermarkets.”

The Guardian revealed in 2022 how hundreds of scientific studies now show that human-caused global heating is driving more frequent and deadly disasters across the planet. Leading climate scientists warned in August that the “crazy” extreme weather of 2023 was just the “tip of the iceberg” compared with the even worse impacts to come.

The study was conducted by the World Weather Attribution group. The researchers used weather data and climate models to compare how droughts have changed in the region since global heating has pushed up temperatures by about 1.2C.

Human-induced climate change compounded by socio-economic water stressors increased severity of drought in Syria, Iraq and Iran

_________

Even the "stable" bits of polar ice are in trouble, new research shows.

The ice shelves extending outward from eight critical glaciers in the northern part of Greenland have lost 35% of their volume and about 33% of their surface area since 1978, according to a study published Tuesday in Nature Communications.

The melt rate for these shelves is accelerating over the last two decades, suggesting an area thought to be more safe than others is also at risk.

"Given the level of climate warming we have been facing during the last two decades, it is hard to say that this is a surprise," Romain Millan, of Université Grenoble Alpes in France and the new study's lead author, told The Messenger.

The melting Greenland ice sheet contributed 17.3% of the observed sea level rise between 2006 and 2018. The ice shelves float on water and act as buttresses for the glaciers on land; if they melt faster or disappear, the northern glaciers could begin to add as much water to sea level rise as the rest of the ice sheet combined.

Much of the massive island's ice melted at a steady pace during the 1980s and 1990s, but the glaciers in the north began to destabilize after the year 2000. Still, in 2018, the losses to the northern glaciers were much smaller than elsewhere.

"In 2022, we detected for the first time in this region a concerning retreat of the Petermann Glacier, which is one of the largest glaciers on the ice sheet," Millan said. "With this new study, we observe that it actually affects all the major glaciers in Northern Greenland."

The increase in melt rate is due primarily to what's known as basal melting, or melting on the bottom of the ice shelves where they touch the increasingly warm ocean waters around Greenland.

Millan said the processes that are weakening the ice shelves are still relatively poorly understood, and that makes it hard to put an estimate on how this could affect sea levels.

"There are still many uncertainties about this today," he said. "It's one of the major scientific challenges in predicting future sea-level changes."

But what is certain is that this research adds to a pile of evidence suggesting that Greenland and Antarctica's ice sheets are in serious jeopardy. A study published in October, for example, showed that the entire Greenland ice sheet, which has the potential to raise global sea levels by more than 20 feet, could begin an inevitable collapse with only a fraction of a degree more warming.

The authors of this new study point out that their study focuses more on the short term and how the ice shelves might affect melting this century, while the October study had a much longer term outlook.

"You could compare what we're doing to meteorology, and what the other paper on Greenland's stability is doing to paleo-climatology," said Eliot Jager, also of Université Grenoble Alpes and a co-author of the new study.

But in both cases, the takeaway is worrying, considering the implications for low-lying coastal areas around the world.

"This widespread weakening of their floating ice shelves, retreat, and dynamic glacier response are alarming signals from these glaciers," Millan said.

"If warming continues, it could significantly increase Greenland's contribution to sea-level rise."

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-023-42198-2

________

- El Niño is getting stronger and that's already making Earth hotter

El Niño continues to strengthen in the tropical Pacific Ocean, which is likely to give global average temperatures a sizable boost going into next year.

Why it matters: El Niño, a natural climate cycle, affects weather patterns around the world, bringing drought to some countries and flooding to others.

Driving the news: NOAA's Climate Prediction Center issued an update this morning that finds El Niño is now in the "strong" category, and there is more than a 55% chance that it will remain this way through the January-through-March period.

- Compared to last month, NOAA slightly increased the likelihood (to 35%) that this event will become historically strong for the November-through-January period.

- NOAA also now expects the event to last through the Northern Hemisphere spring.

The big picture: El Niño can also lead to record warm years by giving a natural bump to human-caused warming, like a person jumping up while on a moving escalator.

- The most recent strong El Niño in 2015-2016 led to a record warmest year, which is on track to be surpassed this year.

- "El Niño is really going to start to bite next year," said Andrew Pershing, VP for science at Climate Central, during a media call on a climate change attribution study.

- Pershing and other outside scientists noted that El Niño is only thought to be responsible for about 0.04°C (0.07°F) of the record warmth seen during the during the 12-month period from November 2022 through October 2023, but that this is likely to grow through 2024.

The ongoing event is already reshaping weather patterns in the Pacific and Indian Oceans, bringing drier-than-average conditions to Indonesia and Australia.

_______

For you climate deniers,…..el nino, la nina and neutral years are all increasing

-

13-11-2023, 08:05 AM #6740

-any-doubts-about-climate-change?

nope, none.

-

13-11-2023, 08:11 AM #6741

^You’re a little slow but good to know you’ve finally come around

Anthropogenic - Caused or influenced by humans. Anthropogenic carbon dioxide is that portion of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere that is produced directly by human activities, such as the burning of fossil fuels, rather than by such processes as respiration and decay.

-

13-11-2023, 08:16 AM #6742Thailand Expat

- Join Date

- Jan 2006

- Last Online

- 23-01-2024 @ 08:31 AM

- Location

- Upper N.East

- Posts

- 2,081

Big yawn...gloom and doom...carry on.

-

13-11-2023, 08:26 AM #6743

-

13-11-2023, 08:34 AM #6744Thailand Expat

- Join Date

- Jan 2006

- Last Online

- 23-01-2024 @ 08:31 AM

- Location

- Upper N.East

- Posts

- 2,081

When has the climate not changed?

-

13-11-2023, 08:36 AM #6745

-

19-11-2023, 05:15 PM #6746

NOAA: October 2023 was the warmest October recorded

NOAA: January – October was the warmest January – October recorded

__________

The Fifth National Climate Assessment is the US Government’s preeminent report on climate change impacts, risks, and responses. It is a congressionally mandated interagency effort that provides the scientific foundation to support informed decision-making across the United States.

A lot of useful information in the Assessment.

Current climate conditions are unprecedented for thousands of years.

Human activities since industrialization have led to increases in atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations that are unprecedented in records spanning hundreds of thousands of years. These are examples of some of the large and rapid changes in the climate system that are occurring as the planet warms.

__________

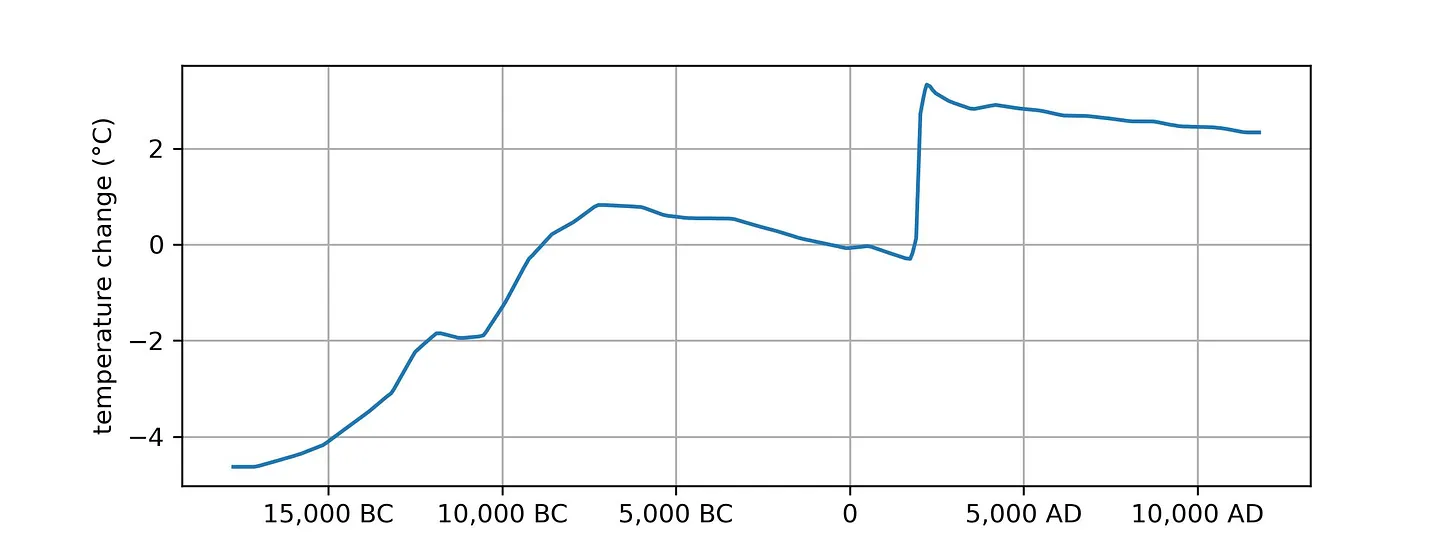

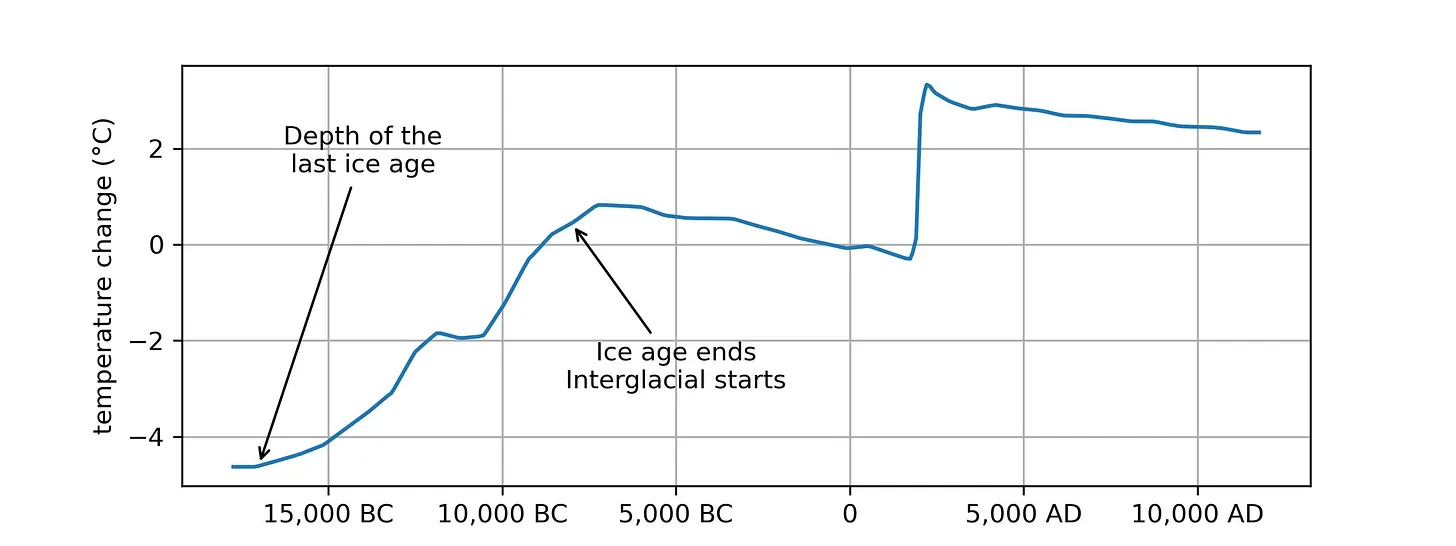

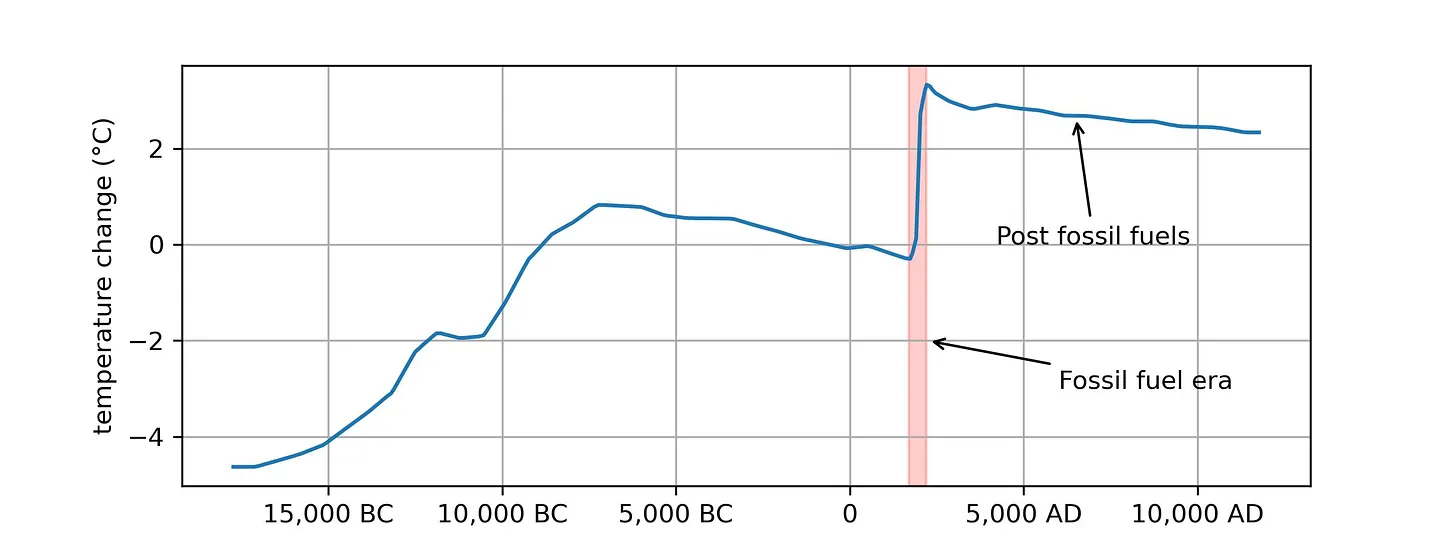

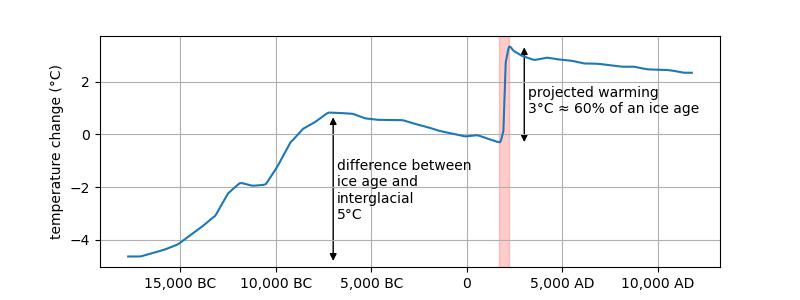

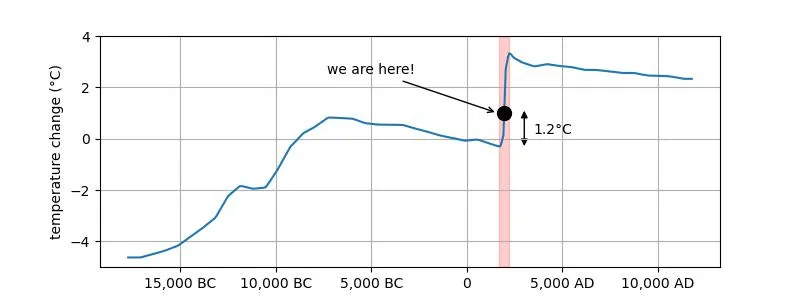

Andrew Dessler - When I give talks about climate change, I start with one particular plot that encapsulates the gravity of our current climate trajectory more starkly than any other I’ve found.

To understand why this plot is so scary, let’s go over what it tells us about past and future climate change.

A journey through 30,000 years

The plot shows the evolution of the climate, starting 20,000 years ago and ending 10,000 years in the future:

The plot begins in the depths of the last ice age, generally referred to in the climate biz as the Last Glacial Maximum. Temperatures then warmed until the ice age ended 10,000 years ago. This is the beginning of the Holocene, the warm and pleasant interglacial period we are now experiencing, characterized by a warm and stable climate that has allowed human civilization to flourish.

The fossil fuel era: A brief spark that causes lasting burns

The trajectory of our climate takes an abrupt detour starting around 250 years ago, coinciding with the dawn of the Industrial Revolution. This is the fossil fuel era — the pink band on the plot. In the grand tapestry of human history, the fossil fuel era will be a brief spark, spanning just a few centuries, yet the repercussions of this period are immense. During the few centuries that we’re burning fossil fuels, we are projected to warm the climate around 3°C given current climate policies.

When the era of fossil fuels eventually ends, whether due to depletion or a concerted shift to sustainable energy sources, the climate will not quickly revert to its pre-industrial state. Rather, the consequences of our brief but intense carbon outburst will linger, with temperatures elevated for 100,000 years.

This is one of the most troubling aspects of climate change: The decisions we make in the next few decades will determine the climate for the next 5,000 generations. If we choose unwisely, people in the future will justifiably be furious with us because we know what we’re doing but we’re doing it anyway.

3°C is bad news

If you think 3°C of warming sounds inconsequential, you’re wrong. Your opinion is based on your personal experience with local temperatures, which do indeed vary a lot. But the global average temperature is very stable, so a 3°C shift is monumental.

We can see evidence for this in the plot above. The last ice age, with colossal ice sheets covering large parts of the Northern Hemisphere continents and sea level 300 feet lower than today, was about 5°C cooler than today. Thus, warming of 3°C is 60% of the temperature change that transitioned us from an ice age into an interglacial. 3°C will literally reformat the surface of the Earth.

Already feeling the heat

We've already seen a global average rise of about 1.2°C, and the impacts are tangible:

And given the non-linear nature of climate impacts, the next increment of warming will be a lot worse than the last one.

But don’t despair, our future is not yet set in stone. We still largely control the fate of our climate. But not for long. If we want to avoid the clear disaster that 3°C of global-average warming represents, we need to address the problem now.

The good news is that we don’t need a magical solution. The challenge of climate change is not rooted in science or technology. We know how to solve this. Rather, it’s a political issue. What we lack is a collective decision to confront and manage this risk. Fortunately, this is something we can solve at the ballot box.

-

27-11-2023, 06:56 AM #6747